Dironna Moore Clarke

Deputy Director, Department of Public Works

Address:

1500 E Franklin St

Richmond, VA

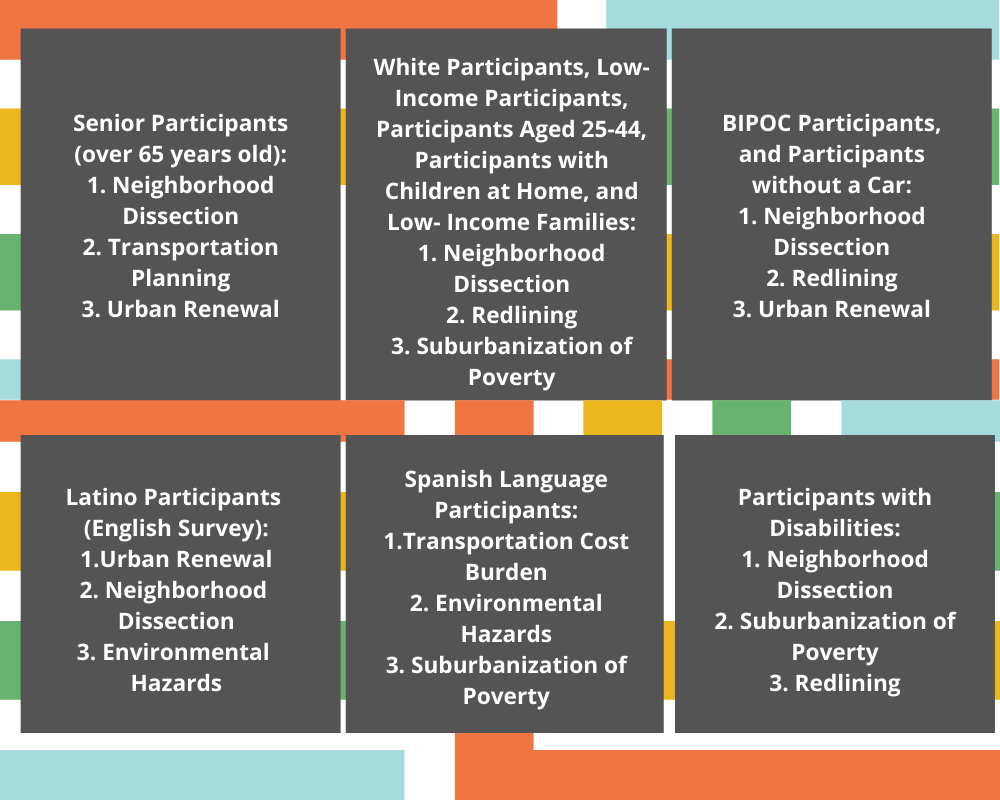

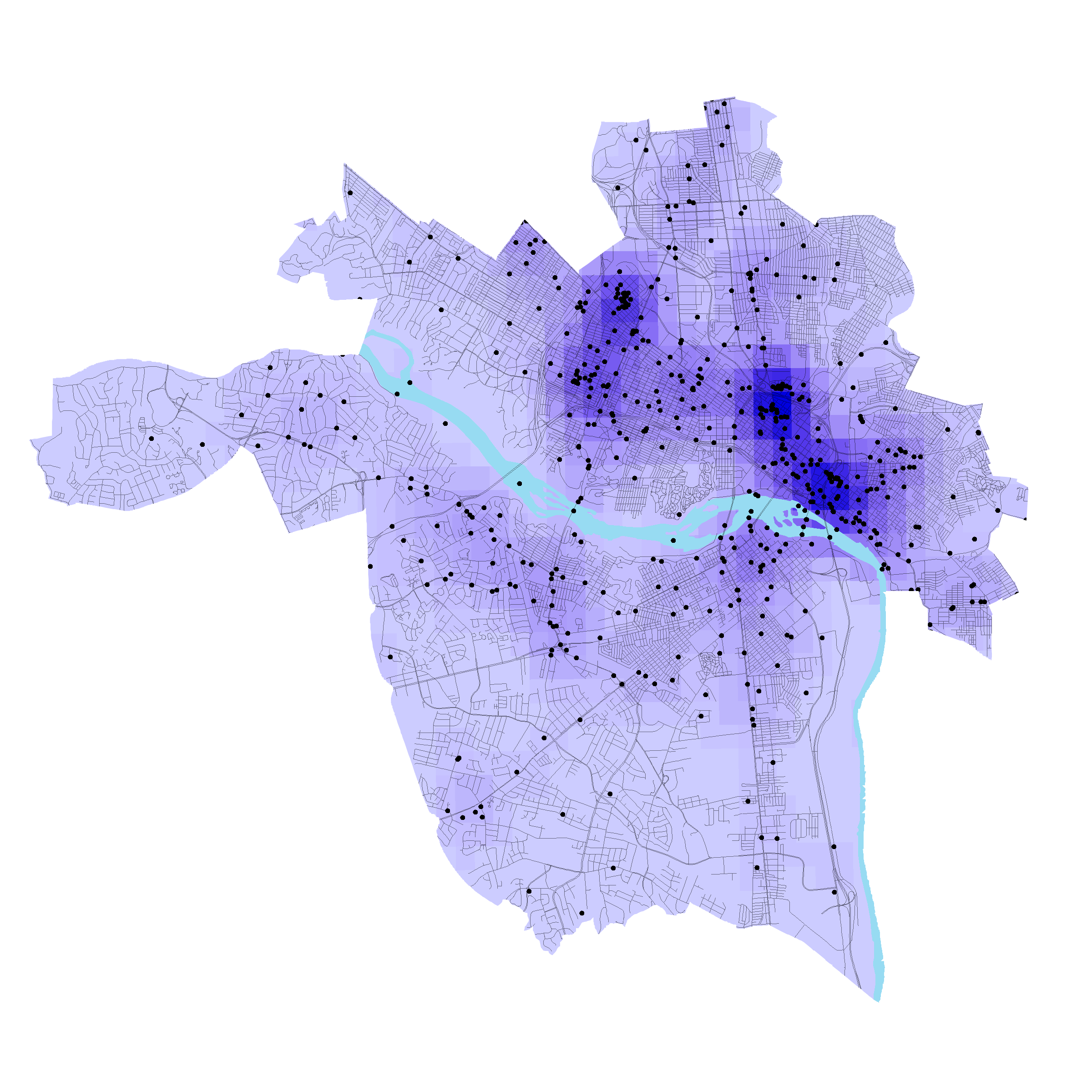

23219 USA

Hours: Mon - Fri (8 a.m. - 5 p.m.)

Phone No. 804-646-6430

Email: Ask Public Works

This policy guide first and foremost describes the policy that Richmond will adhere to when making transportation decisions and investments. It is a statement of the fundamental ideology and set of guidelines, written and shaped by thousands of Richmonders, that will inspire and mediate programs and investments for the future.

The contents of the document are below, and can be navigated through the tabs above, which mirror the chapters from the PDF version of the guide.

Introduction

Defining equity

Richmond’s Transportation and Land Use Injustices

- History of Racial and Socioeconomic Transportation and Land Use Injustices in Richmond

Existing Plans and Planning Practices

- The State of Transportation Planning

- Local Context

- Regional Context

- State Context

- Federal Context

Public Outreach and Best Practices

- Best Practices in Equitable Outreach

- Best Practices in Equity Surveying

Developing Equitable Mobility

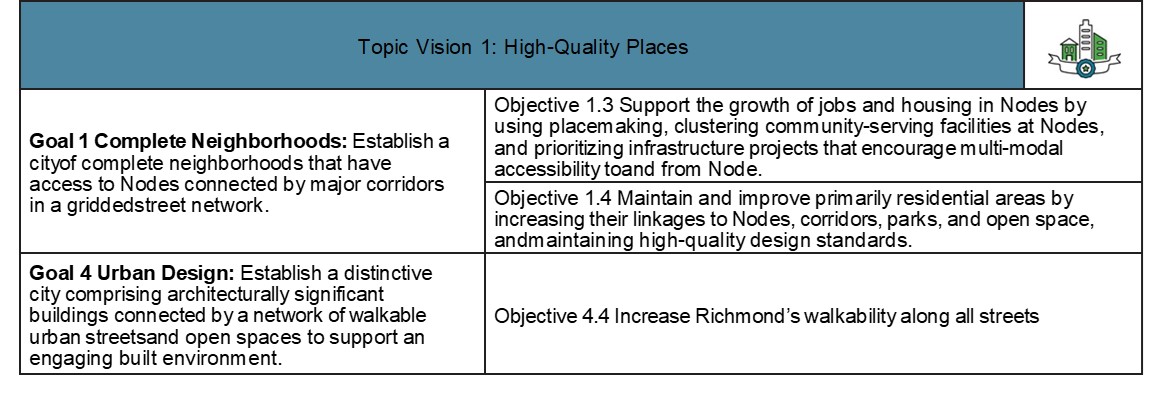

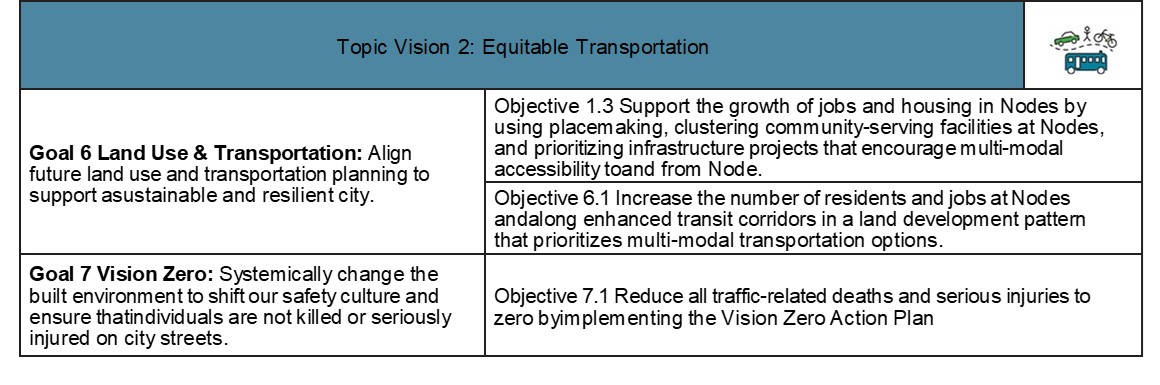

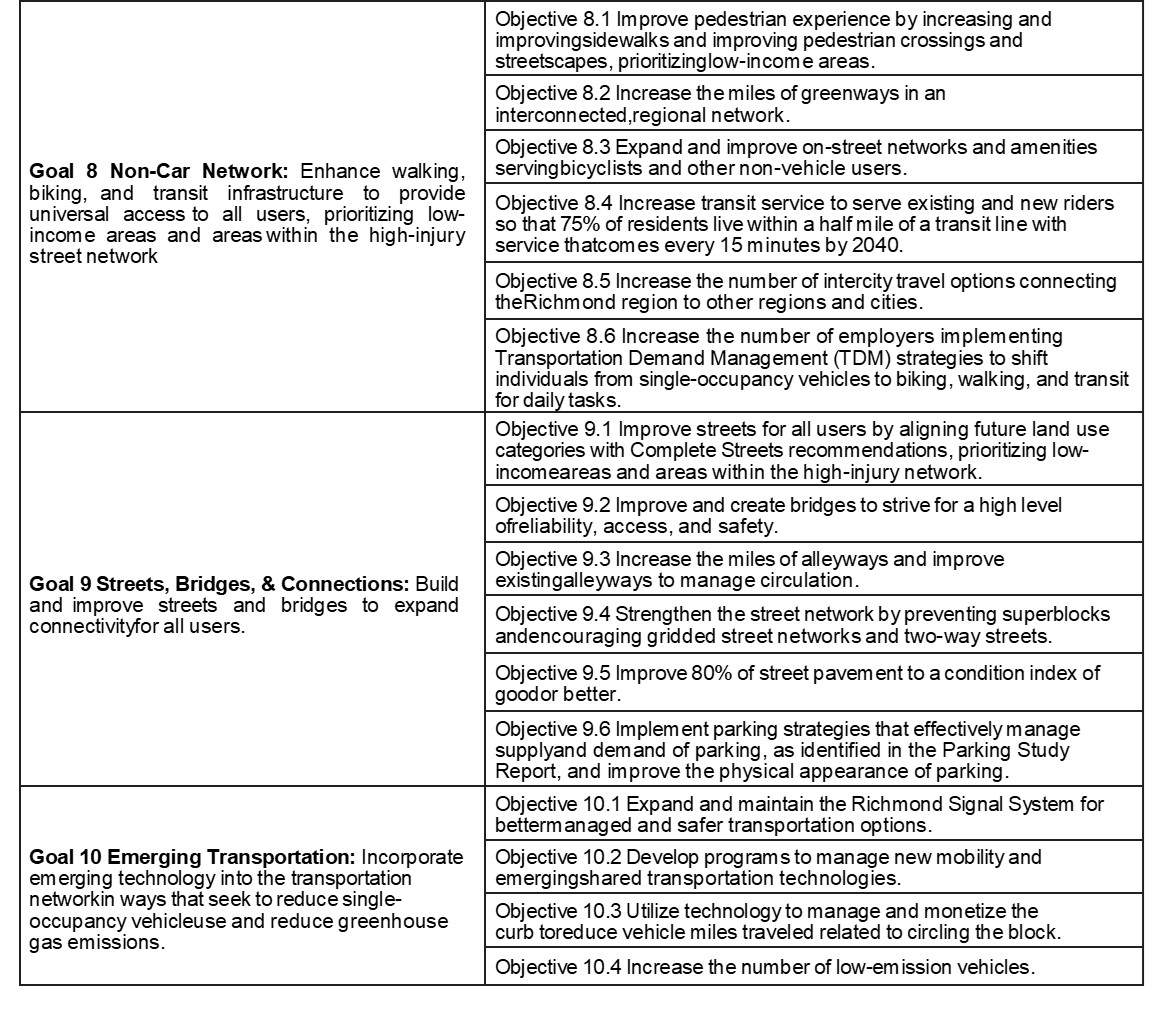

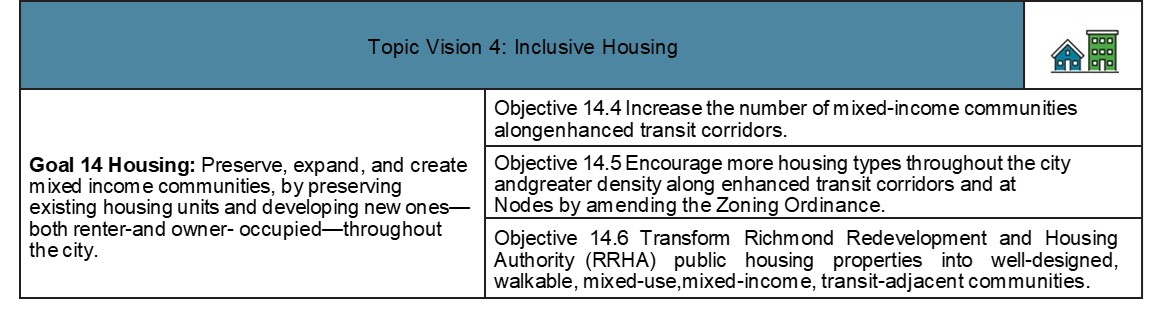

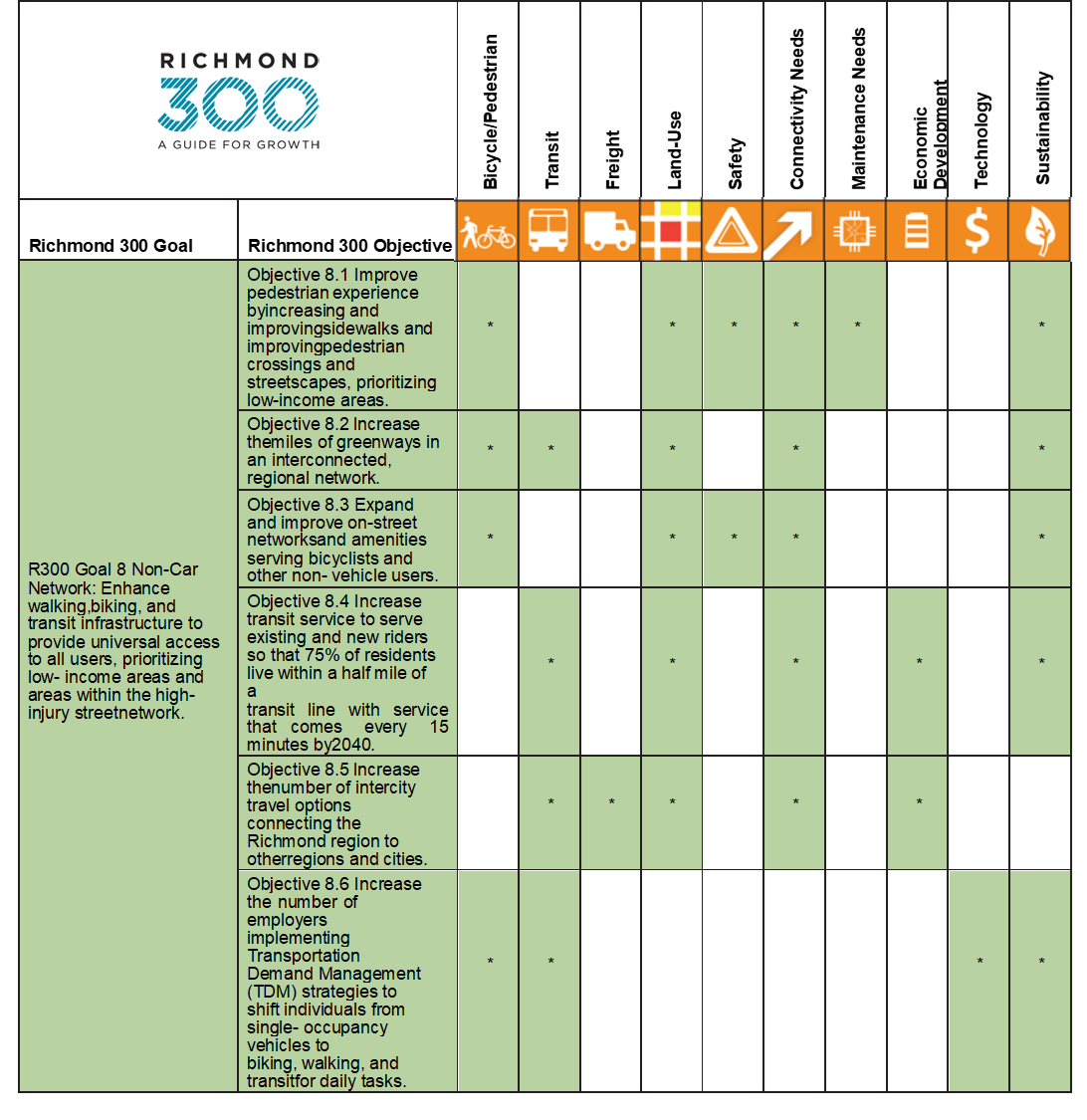

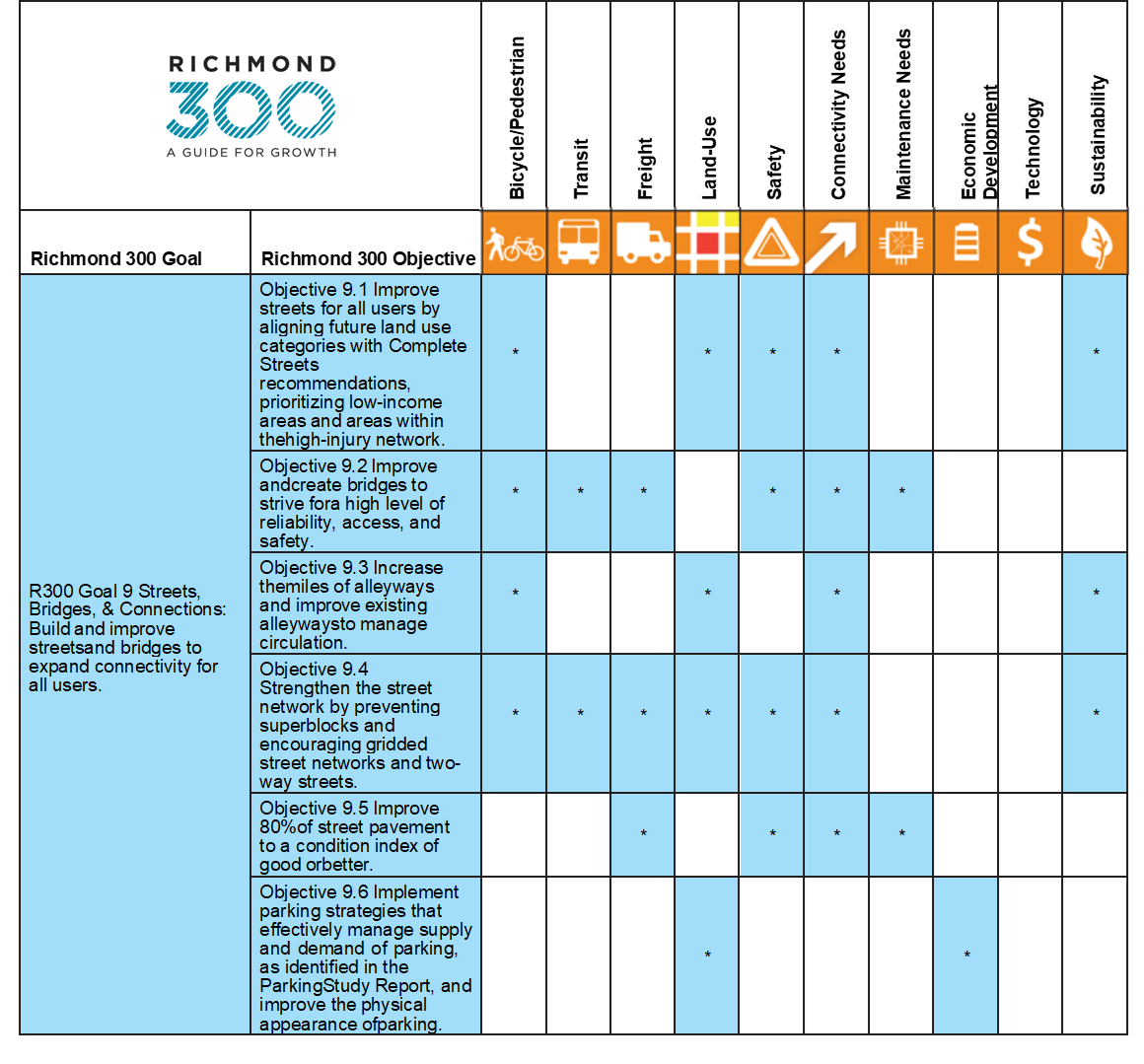

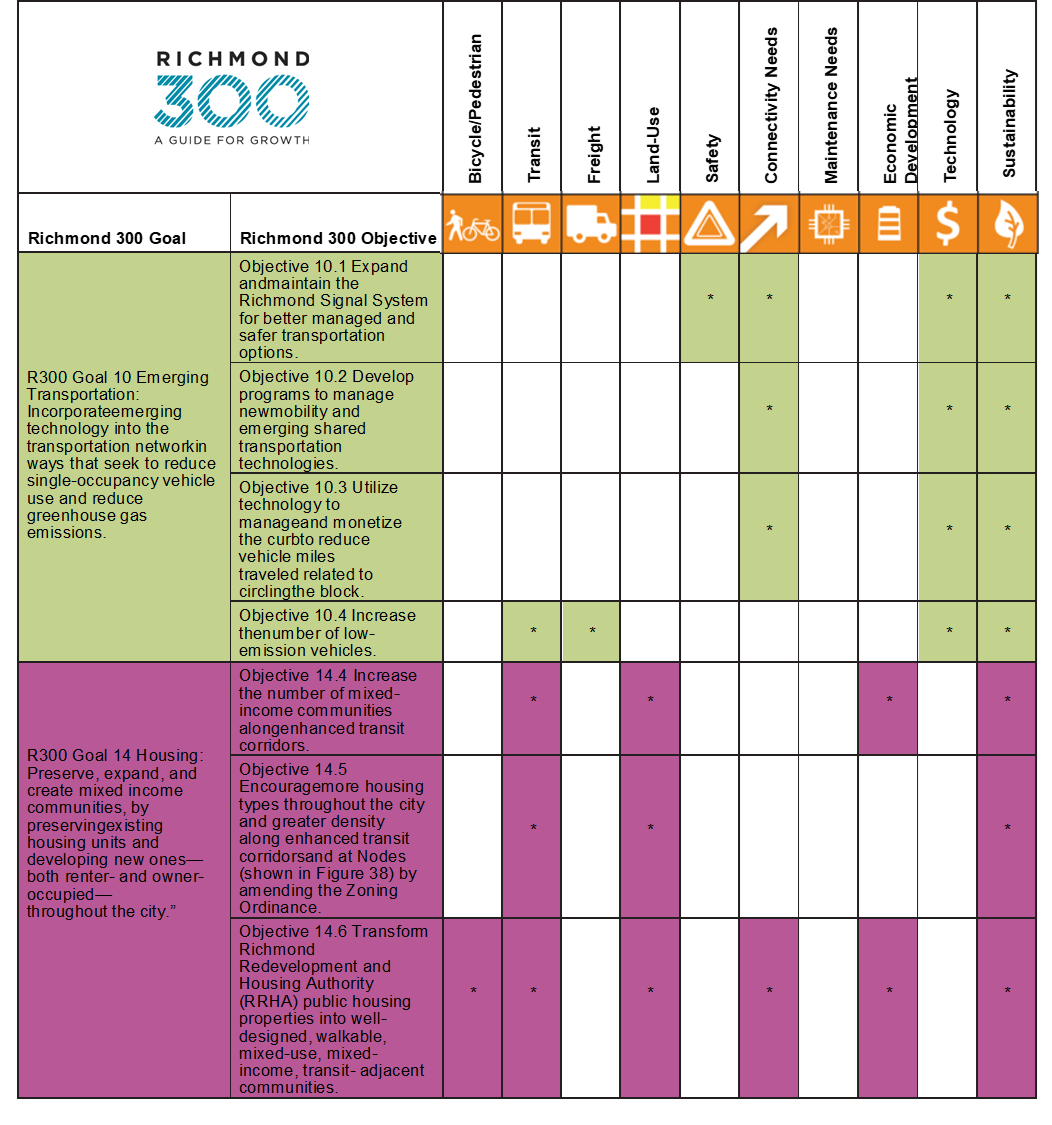

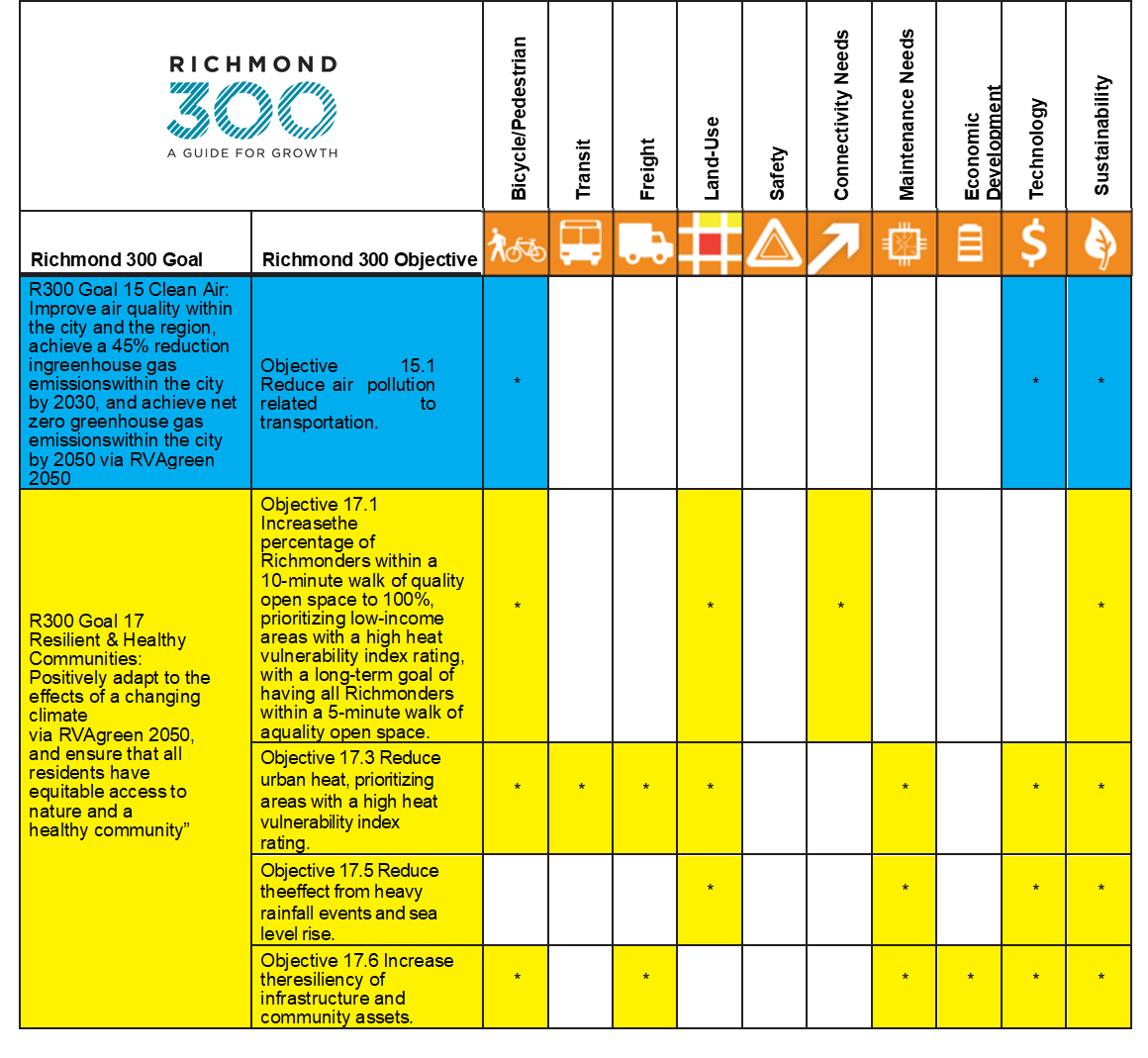

- Richmond 300 Vision, Goals, and Objectives

- Transportation Investment Needs Categories

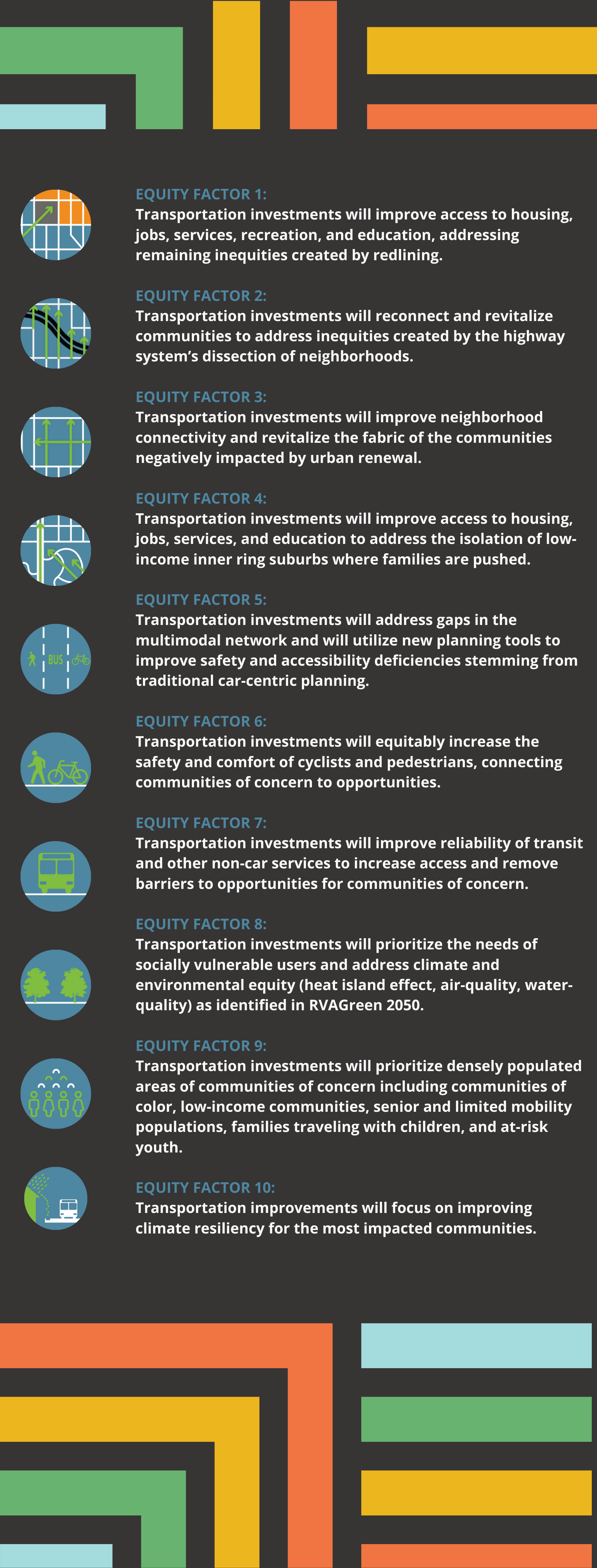

- Equity Factors

- Guiding Principles

- Using this Policy

Equity Planning Research

- Equity Outreach Research

- Equity Scoring Research

- Equity Data Collection Research

“Regardless of what zip code you live in or work in, you should feel like you belong right here in this city - that’s the whole city - it is your home and we will make it a reality with equity within transportation.”

-Mayor Levar Stoney, September 2020

Figure 1. Richmond has a long history of systemic racial oppression with an equally rich history of Black-led resistance. This image depicts a 1960 sit-in staged by Virginia Union University students. The sit-in protested dining segregation in a department store. Source: Richmond Times Dispatch

In light of the changing City environment, culture, and social needs, the City of Richmond (COR) has determined it is vital to update its policy guidance for multimodal transportation. The basis for this policy guide, coming from our citizens and our elected leadership, is to apply an equity lens as the central factor for understanding our multimodal transportation needs. How to achieve equity in transportation and defining what equitable transportation looks like in the eyes of Richmonders is the primary focus of the policy guide. This plan, “Path to Equity: Policy Guide for Richmond Connects,” is intended to direct actions that will ensure the equitable movement of both people and goods, with an emphasis on creating great places for everyone.

The policy guide first and foremost describes the policy that Richmond will adhere to when making transportation decisions and investments. It is a statement of the fundamental ideology and set of guidelines, written and shaped by thousands of Richmonders, that will inspire and mediate programs and investments for the future. A policy as defined by Merriam Webster can be:

“prudence or wisdom in the management of affairs … a definite course or method of action selected from among alternatives and in light of given conditions to guide and determine present and future decisions…a high-level overall plan embracing the general goals and acceptable procedures especially of a governmental body.” (1)

This guide is intended to serve all of those defined functions. It also serves as a document to educate and bring awareness to the history and context of inequity in transportation in Richmond’s past and present. The first step to action is knowing – this policy guide’s dual purpose as an education and awareness tool will lead to a collective defining of the problems within the transportation network. COR aims to articulate how the identified inequities in transportation lead to social inequities in multiple areas of daily life, including health, wealth, and well-being.

At the core of this plan is also the recognition that inequities are not contained only in transportation, and the realization of the actions needed to achieve equitable transportation falls on all City departments, as well as on state and federal planning partners. It is founded in the knowledge that we did not get here overnight, and these deep rooted systemic issues will not be resolved overnight. The work will take a continued adherence to equity goals, and the continued momentum of collective social and political will, charged by the Citizens of the Richmond region, to make real change. This policy guide is but one step in the right direction, part of an overall shift in the culture of City government that centers on achieving equity.

(1) 1. Merriam-Webster, “Policy,” Merriam-Webster, December 30, 2021, https://www.merriam-webster.com/.

The second and third chapters highlight what equity is and what that means in the context of Richmond’s present state of practice and planning. The next chapter aims to highlight the problematic injustices caused and/or perpetuated by a cascade of intertwined transportation and land-use policies and practices of the past 150 plus years. These injustices harm our low-income communities and communities of color the most, and this plan aims to take ownership of local government’s role in creating and perpetuating these injustices. This policy guide also describes how those past injustices are still felt today, and how the limits to opportunity founded in these injustices are unacceptable and must be corrected. It lays out how the city, state, and federal governments have played a major role in creating the inequities faced today. It acknowledges the structural and embedded racial biases in policies past and aligns Richmond’s current transportation policy with anti-racism philosophy.

Chapter 4 lays out the context of current policy and programming (i.e. how things get funded, built or implemented), and what barriers have to be overcome at all levels of planning outside of just the Richmond Capital Improvement Program (where the city allocates its transportation dollars). The descriptions of the challenges to equity in transportation in chapter 3 are meant to lay an overarching path to achieving true equity. The City must work with its local, regional, state, and federal planning partners to fix the problems of inequity in transportation.

Chapter 5 goes on to describe some of the best practices considered when crafting this policy guide and the outreach that created it. Several elements are consistent with non-profit, academic, and federal/state guidance on executing planning equitably. Feedback from this initial policy guide outreach will also influence the techniques deployed in future planning. The COR staff fully recognize that equity planning is an evolving practice with new guidance being developed as the dialogue between Cities and those at the forefront of the current social justice movements continues. The COR is prepared to continue in this dialogue as the Richmond Connects plan is developed. The outreach completed and described herein strived for excellence in equity and implemented methods that sought to elevate traditionally underserved populations into a position of decision making power.

Chapter 5 gives a detailed look into the process used to create this policy guide and includes a description of the outreach methods designed to equitably engage residents. The “Path to Equity: Policy Guide for Richmond Connects” strives to be innovative and consider methods for equity planning and engagement from across the country.

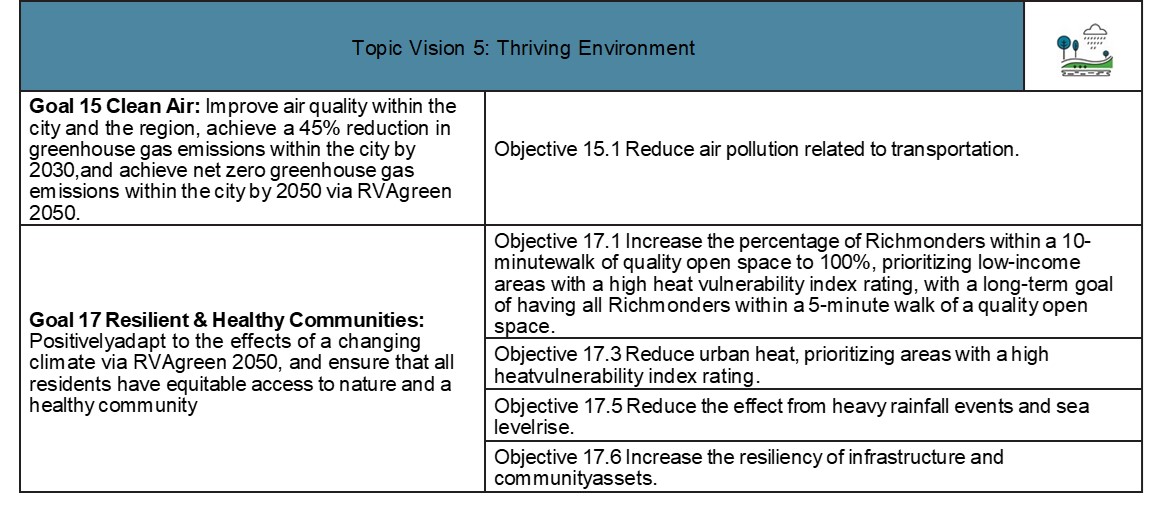

Chapter 6 spells out the actual policy language itself. This chapter reiterates the vision, goals and objectives set for equitable transportation in the Richmond 300 Master Plan: A Guide for Growth. This chapter then includes a new set of policy statements called Equity Factors, which are designed to hone in on resolving targeted inequities. These statements will be used in addition to the Vision, Goals and Objectives from the Master Plan. These were crafted using survey data from Richmond residents, research on history and status of inequity in transportation today, and in consultation with an advisory committee and steering committee. These statements are designed to bring clarity to what Richmond sees as the path to equity in transportation. They articulate what future transportation investments will do. If these equity factors are upheld when making funding decisions, transportation will move the needle to a more equitable future for all Richmonders. These factors are listed on this page and also included below as this new policy language was a major focus of the outreach and should be highlighted.

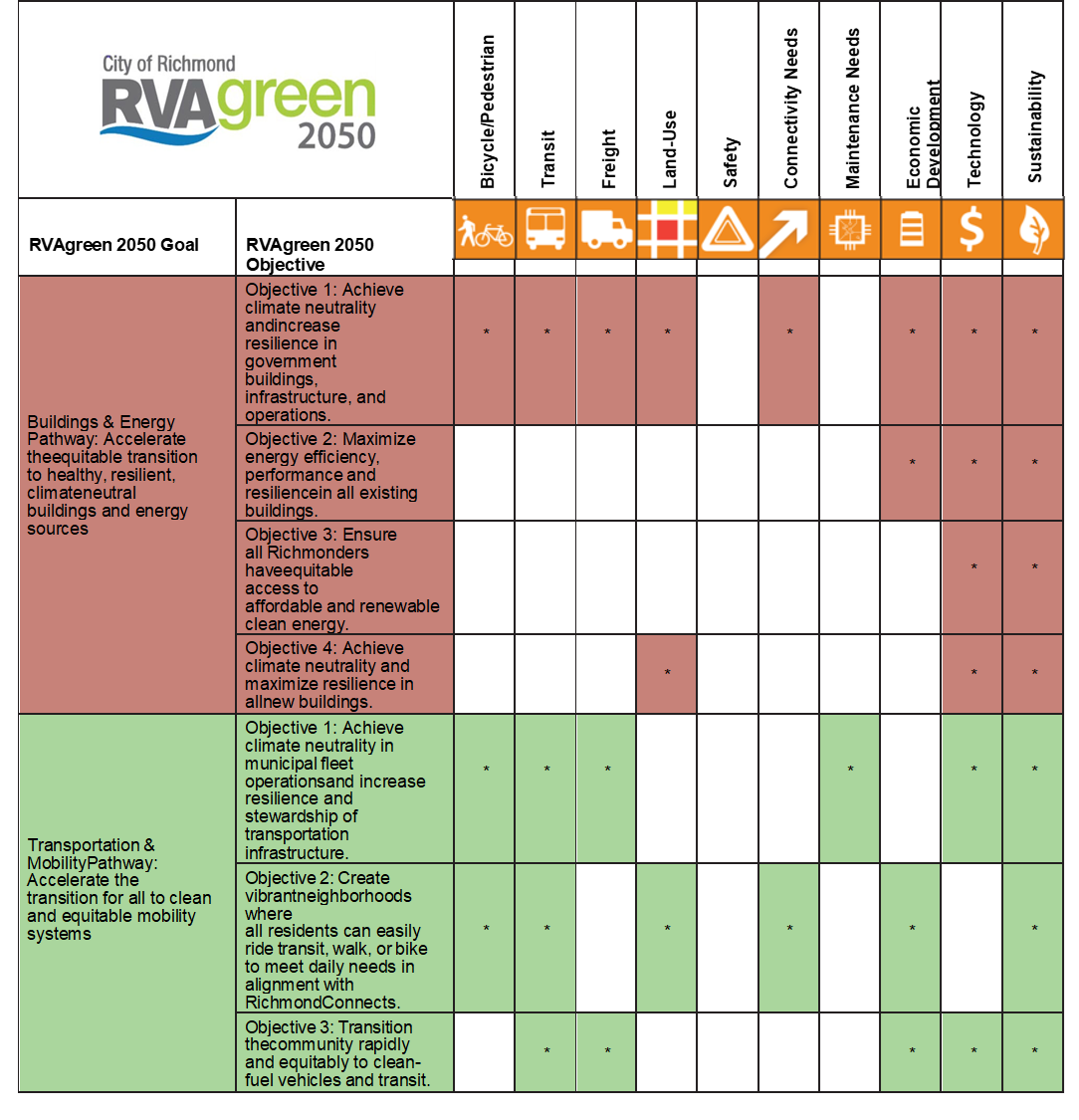

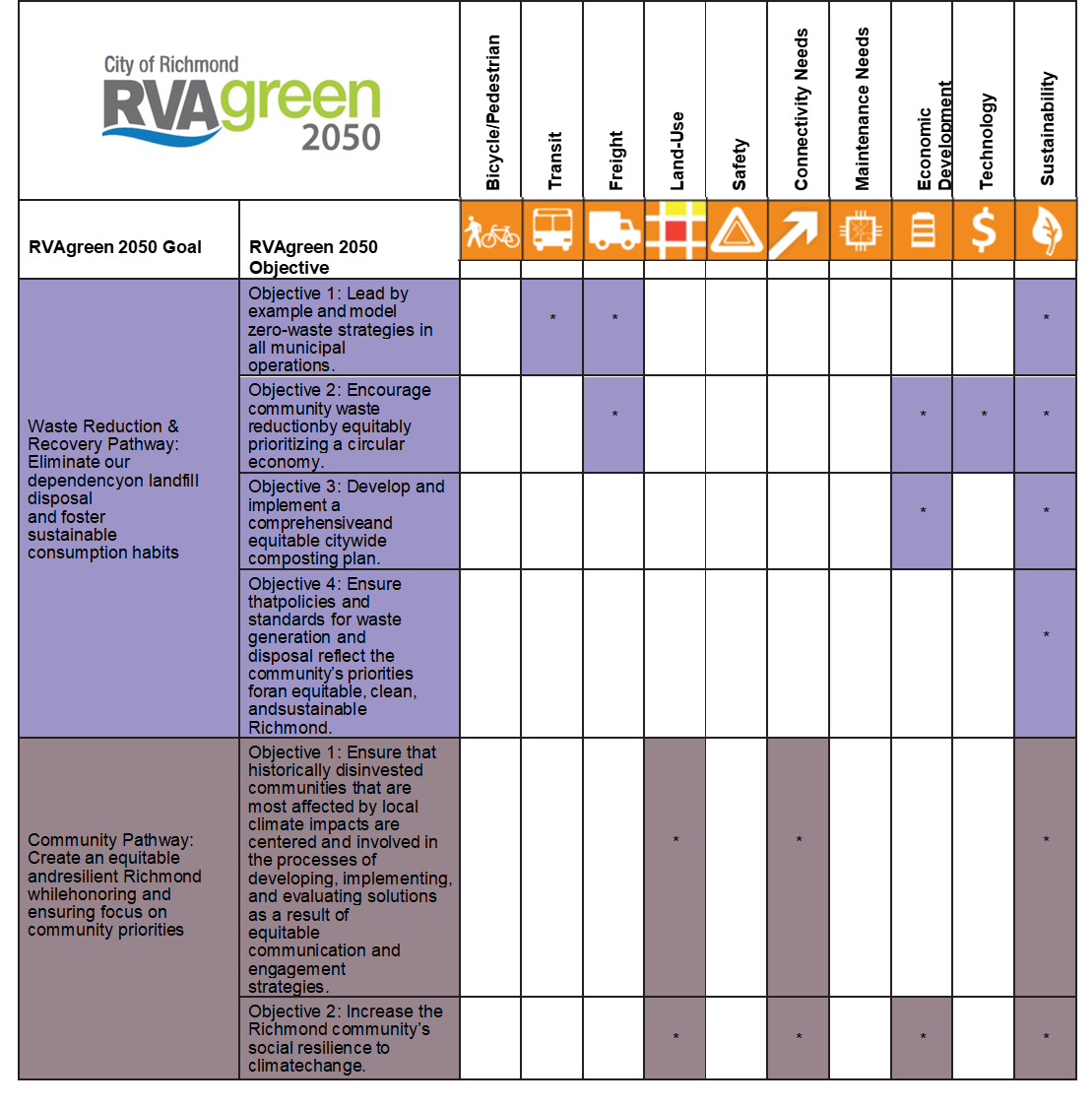

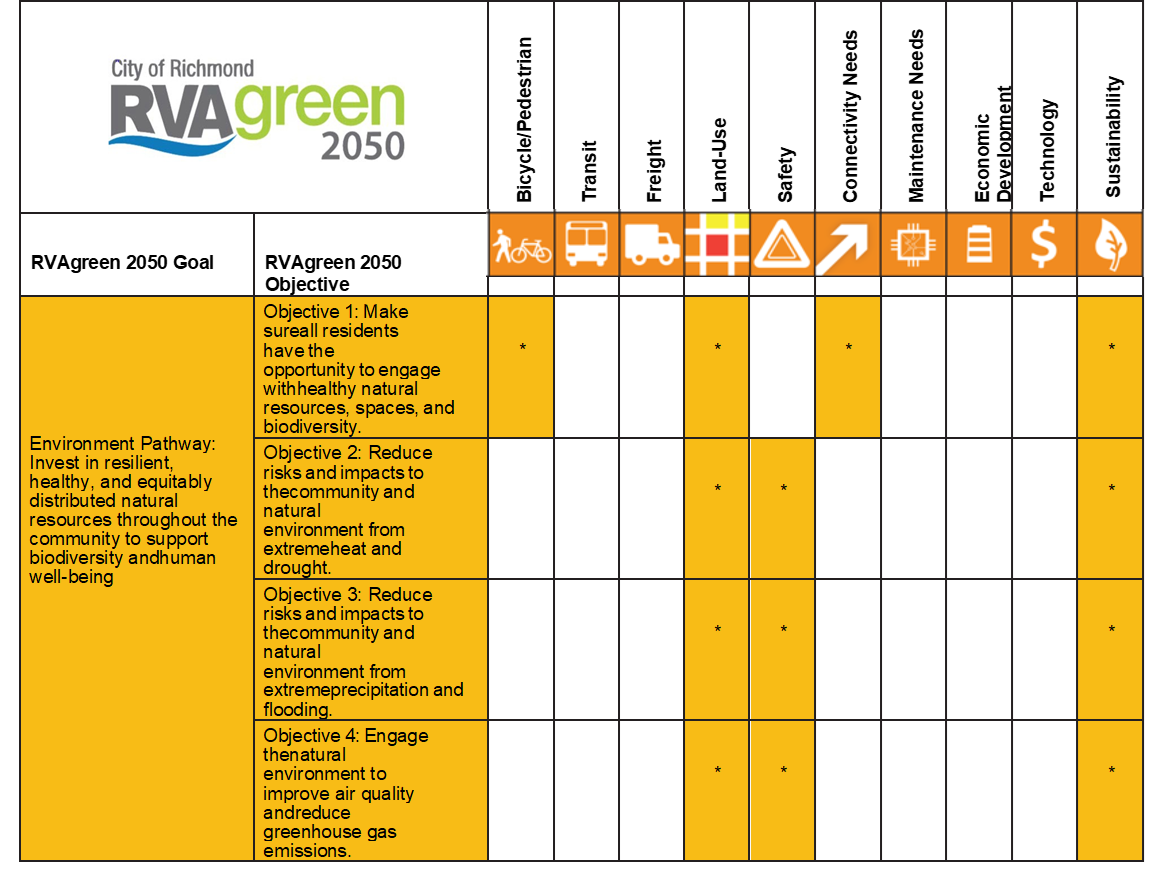

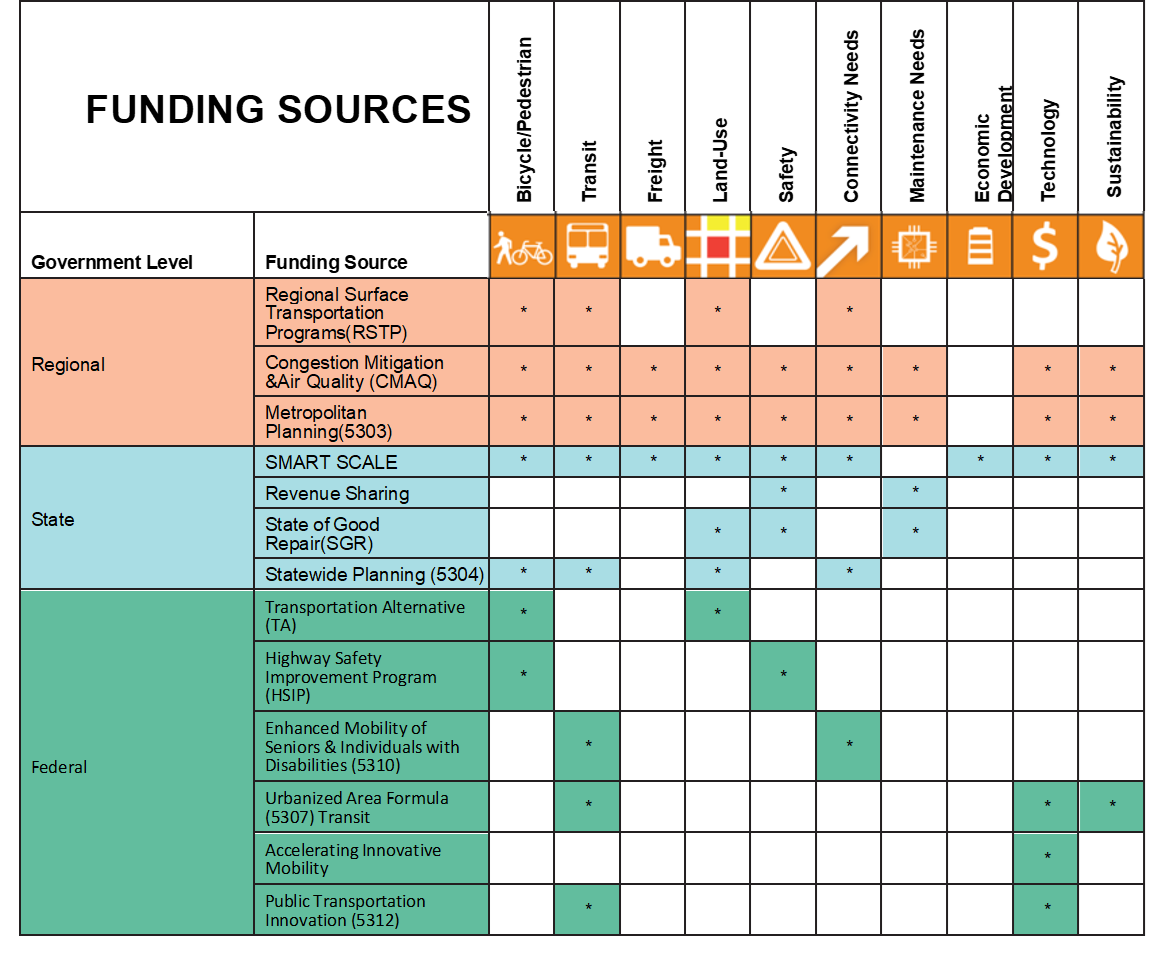

Chapter 6 also establishes a set of investment need categories designed to show the alignment between the Richmond 300 and RVAGreen2050 policy and the various types of transportation needs that may arise in the full Richmond Connects update. This linkage is vital to meeting the various requirements for multimodal transportation planning and is key to illustrating the connections to funding categories from which most projects will be implemented.

The objectives from the master plan and the equity factors stated in this chapter describe what needs to be achieved. Chapter 6 also articulates critical considerations for how the objectives and equity factors are ultimately implemented in the form of Guiding Principles. These were created based on literature review, comments from the survey, and were substantiated by the advisory committee.

Chapter 7 gives an overview of the case studies and guidance documents that were considered in the development of this plan and the outreach for it. This section is designed to assist other localities in implementing this type of planning and also to document the evolving practice of equity planning in the transportation realm. By the time this plan and the Richmond Connects planning compendium are complete, there will surely be even more equity planning documents to consider. This section will serve as a snapshot of the planning context considered at the time of the plan development.

In total, this document will lay the policy framework for funding decisions and all subsequent transportation planning efforts anticipated by the COR. It is first and foremost intended to guide the development of the Richmond Connects plan compendium, including a Richmond Connects Mobility and Accessibility Action Plan (RC-MAAP) and a Richmond Connects Scenario Plan. COR has made progress on many of the objectives and recommendations of the 2013 Richmond Connects and has since completed a new master plan, Richmond 300. The Richmond 300 master plan lays

These documents will lay out the short and long term multimodal transportation needs within a framework that gives additional weight to equity as laid out in this policy guide. The objectives and equity factors described in chapter 4 will lead to metrics designed to assess transportation and equity needs across all of Richmond. The metrics themselves will be developed through additional rigorous outreach and are not laid out in this plan, though the policy framework responsible for guiding the metrics is contained herein. The Path to Equity Policy Guide, and the future Richmond Connects plan, will lay out a plan for equitable transportation - for the people and by the people of Richmond.

This overarching planning process is designed to empower communities and create opportunities through the creation of thoughtful multimodal connections. It is the intention of the City to articulate in this document the “definite course of action” to move the needle towards an equitable future for all of Richmonders.

It is designed to lay out a path for the future, a path to equity.

In June 2021, Richmond City Council adopted a road map to a more inclusive and thriving city: The Richmond Equity Agenda. This document establishes ten guiding principles for achieving equity and defines equity in the City of Richmond as:

“The empowerment of communities that have experienced past injustices by removing barriers to access and opportunity.” |

The Richmond Equity Agenda has ten Guiding Principles to improve equity over the next ten years. Those ten principles are:

-

Addressing and preventing health disparities

-

Housing as a vaccine for poverty

-

Ensuring equitable transit and mobility for residents

-

Building community wealth to combat economic inequity

-

Supporting and caring for our children and families

-

Creating equitable climate action and resilience

-

Reimaging public safety

-

Telling the real history of Richmond

-

Strengthening community engagement and trust

-

Utilizing economic development to create economic justice

As part of the “Ensuring equitable transit and mobility for residents

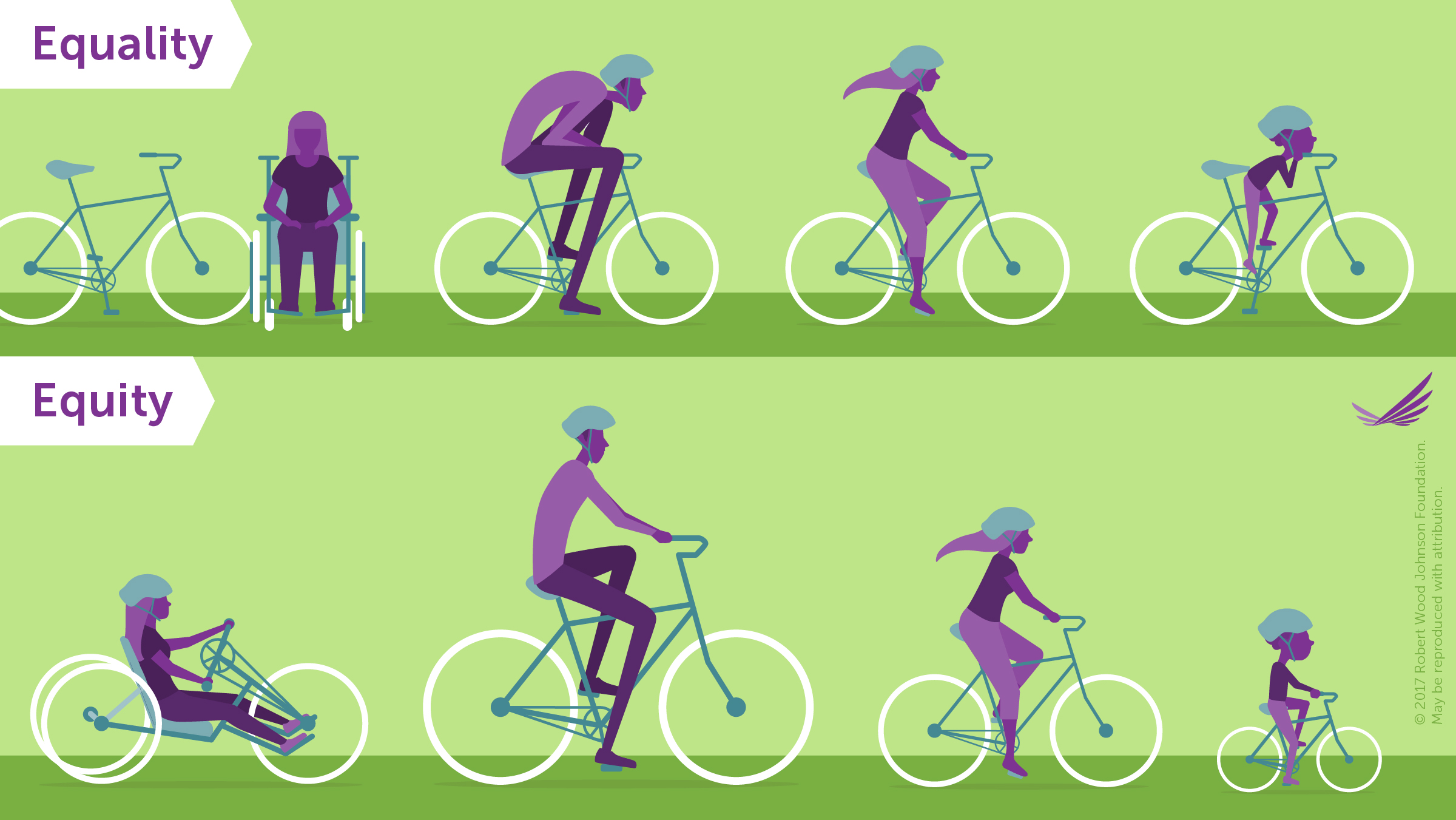

To illustrate equity, people often compare it to equality, illustrated in the Figure below. If pursuing a state of equality, every person – no matter what their individual needs are – receives a bicycle. When pursuing equity, every person is given a bicycle that fits their specific needs.

All levels of American government have participated in the systemic oppression of BIPOC and low-income groups in the past with an increased scale of government-funded oppression in the 20th century. Transportation and land use policies have economically stymied BIPOC and low-income neighborhoods, cut them off from essential services, or entirely demolished them. Having been stripped of their assets and wealth-building potential in the past, BIPOC and low-income people have entered into generational poverty and experience disadvantages lasting far longer than the policies that created this imbalance. Programs that target access improvements and new opportunities for the disadvantaged can be defined as equitable and the success of these programs can be defined as justice. A truly equitable transportation network will be in which no group of persons bears any more or less of the burden of transportation costs, one in which no one group bears the benefits more or less than any other group of persons, and one in which no one group faces more or less barriers to accessing opportunities than another. An equitable network will be achieved when a person’s race, income, or characteristic of personhood cannot be used as a predictor of life outcomes, and outcomes for all groups are improved (2). In Richmond, creating an equitable future will require asset- based framing and a broader shift to antiracist action.

(2) Julie Nelson, “Advancing Racial Equity and Transforming Government,” https://www.racialequityalliance.org/viewdocument/advancing-racial-equity-and-transfo

Deficit thinking is a concept where the privileged class perceives disadvantaged classes as not working hard enough to achieve the same success that the privileged class is enjoying. This line of thinking neglects to take into account the limitations caused by wealth and class in America.

Deficit thinking leads to a cycle where the privileged class does not advocate or support methods of aid that would provide the disadvantaged classes with the resources they need due to the privileged class believing that the disadvantage is internal to the individual and not external. Providing these resources to the disadvantaged is equity. When analyzing the root cause of inequity, it is important that governments not construct or determine indicators with a deficit thinking mindset. The conclusions should be that structural racism drives discrepancies in equity, not that the actions of individuals create their own inequality (3).

A new approach to counter deficit thinking is called asset framing. Asset framing uses language to focus on the successes and contributions of a traditionally marginalized group. Asset framing highlights the goals and ambitions of a group rather than their challenges. The rationale behind this approach is that language that emphasizes a group’s challenges will psychologically impact a listener and cause them to see the group in a more negative manner. Asset framing is useful for empowering traditionally marginalized groups. However, asset framing should not be used as a way to avoid the discussion of systemic oppression and ongoing injustices (4).

(3) The Municipal Policy Network, “Introduction: Embracing a Racial Equity Approach,” https://localprogress.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/Intro-Racial-Equit….

(4) Workforce Matters, “A Reflection on Asset-Framing for Workforce Development,” June 8, 2021, https://workforce-matters.org/a-reflection-on-asset-framing-for-workfor….

Structural racism is a system where policies, institutions, cultural depictions, and societal norms reinforce and perpetuate racial group inequality.(5)

Our culture today and historically has provided certain privileges for people and practices associated with whiteness. So to have disadvantages been associated with color. A cultural example of structural racism can be found in depictions of Santa Claus. While depicted almost exclusively as white, the character is based on St. Nicholas – a Christian monk from the 3rd century who was born in modern-day Turkey (6). One could argue that our culture’s association of whiteness as a privilege resulted in the character being presented as white rather than as a person of color. An institutional example of structural racism can be found in the documented preference of employers to white-sounding names. The Harvard School of Business found that when BIPOC candidates who removed references that would reveal their race in their resumes were more than twice as likely to receive an interview than if they kept the race references in (7). Because structural racism is not something an individual chooses to participate in, it is easy to believe that racism is individualistic and that to solve the problem abject racists should be reformed or removed from power. This is an important action, but racism is a systemic evil in America. Slavery was the norm less than 160 years ago. The guiding legal document – the U.S. Constitution – remains mostly intact despite being drafted for a nation intending to use slave labor indefinitely.

The antidote to racism is defined as antiracism. To be antiracist is to actively fight against racism. According to the National Museum of African American History and Culture, racism manifests in four forms:(8)

- Individual Racism: The beliefs, attitudes, and actions of individuals. These beliefs may be unspoken in public but guide the actions and dictate the biases of the individual.

- Interpersonal Racism: The interactions between individuals where racism is outwardly displayed. This includes slurs, biases, and hateful speech and actions.

- Institutional Racism: Organizational-level racism. This includes workplace discrimination, unfair policies, and biased practices that result in preferential treatment for white people.

- Structural Racism: The overarching system of racial bias across society.

Bias exists among all people and could be defined as the evaluation of one group against another. Bias can be split between explicit and implicit. Explicit bias – the outward and obvious expression of one’s biases – is generally not acceptable in American culture. Implicit bias, however, is deeply ingrained into our culture, institutions, and systems (9). Implicit biases are the internal, unidentified prejudices that drive our actions. Antiracism addresses these implicit biases by bringing them to the surface. Table 1 explains the two types of bias.

Table 1. Explicit and Implicit Biases

Antiracism requires a conscious understanding of how race privileges some and disadvantages others. At the individual level, privileged groups should educate themselves on race relations and, more importantly, listen to those disadvantaged by race when they express grievances. This understanding will help individuals know when racist biases or actions are present and help them act in an antiracist way. Incorporating antiracism in all aspects of one’s life helps make bigger changes at the institutional and structural levels.

COR, through the Richmond Equity Agenda, has taken the first step in developing antiracist policies. When carried out, the ten principles will each address structural racism that impacts Richmonders today. This plan, Path to Equity, seeks to incorporate antiracism into the City’s transportation planning to address the structural racism present in the mobility realm.

(5) The Aspen Institute, “Glossary for Understanding the Dismantling Structural Racism/Promoting Equity Analysis,” https://www.aspeninstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/RCC-Structural-Racism-Glossary.pdf

(6) History.com Editors, “Santa Claus,” History, December 14, 2021, https://www.history.com/topics/christmas/santa-claus.

(7) Dina Gerdeman, “Minorities who ‘whiten’ job resumes get more interviews,” Harvard Business School, 17 May, 2017, https://www.library.hbs.edu/working-knowledge/minorities-who-whiten-job-resumes-get-more-interviews

(8) “Being Antiracist,” National Museum of African American History and Culture, https://nmaahc.si.edu/learn/talking-about-race/topics/being-antiracist.

(9) “Being Antiracist,” National Museum of African American History and Culture.

The Covid-19 pandemic required government response by March of 2020. The pandemic has caused extreme financial, psychological, and emotional hardship for many in the city. The Richmond Redevelopment and Housing Authority (RRHA) and the Greater Richmond Transit Company (GRTC) have maintained two significant equitable practices through the pandemic.

RRHA has frozen evictions since 2019, after receiving widespread attention for their high rate of evictions in the city. Documents show that RRHA initiated eviction lawsuits for tenants owing as little as $50 (10). With an average annual income of less than $12,000, the eviction of Richmonders living in RRHA properties could lead to exponential debt increase or even homelessness (11). Following community backlash, RRHA initiated an eviction freeze. This freeze has been extended several times, lasting through the pandemic thus far. However, the eviction moratorium is set to expire January 1, 2022. RRHA has stated that residents who have applied for rent relief will not be evicted. Residents who have not applied for rent relief and are two months behind on their rent are subject to eviction (12).

GRTC initiated a free fare system at the onset of the pandemic. The free fare was intended to both eliminate contact between bus drivers and riders as well as providing relief for the significant portion of riders making less than $25,000 a year. GRTC has extended the free fare system into 2025 and is working with both the Department of Rail and Public Transit (DRPT) and the Central Virginia Transportation Authority (CVTA) to study the possibility of offering free fares indefinitely (13).

(10) Mark Robinson, “RRHA to resume evictions from public housing in August,” Richmond Times-Dispatch, July 4, 2021, https://richmond.com/news/local/article_bf130fab-b12f-5fd4-88c0-7d8c2b71ef25.html

(11) Mark Robinson, “RRHA to resume evictions from public housing in August.”

(12) ibid.

Much of Richmond’s inequities can be traced to transportation and land use decisions in the past 100 years.

These injustices, detailed in the following pages, were often encouraged by the federal government through funding programs. While much of the policy discussed in this section is rooted in the more recent past, Richmond’s complex history includes many atrocities we must also acknowledge as part of the foundation upon which these more recent injustices lie. We must acknowledge the unjust displacement and forced assimilation of indigenous communities including the Powhatan, Chickahominy, and Youghtanund peoples in the region. We also must not hide from realities created by Richmond’s roots in slave labor and history as the Capital of the Confederacy. The culture and social structures we have today are bound to this past, and this context must continue to be called out and the cultural trauma healed for progress to be made.

The transportation and land use injustices of the past have ultimately cut off Richmond’s urban poor and BIPOC residents from essential services and basic quality of life amenities that wealthier, whiter neighborhoods enjoy nearby. These injustices are all linked in a complex web, often compounding, resulting in concentrations of extreme poverty and urban decline.

The following sections detail Richmond’s major injustices as they relate to transportation and related land-use policies of the past.

This list is not inclusive of all injustices that Richmonders face. It does not include injustices faced in the criminal justice sector, the financial and banking regulatory sectors, the public assistance or social services sectors, or the myriad of other government sectors, and does not aim to be exhaustive. It aims to describe the major injustices identified by the study team related to public policy and transportation

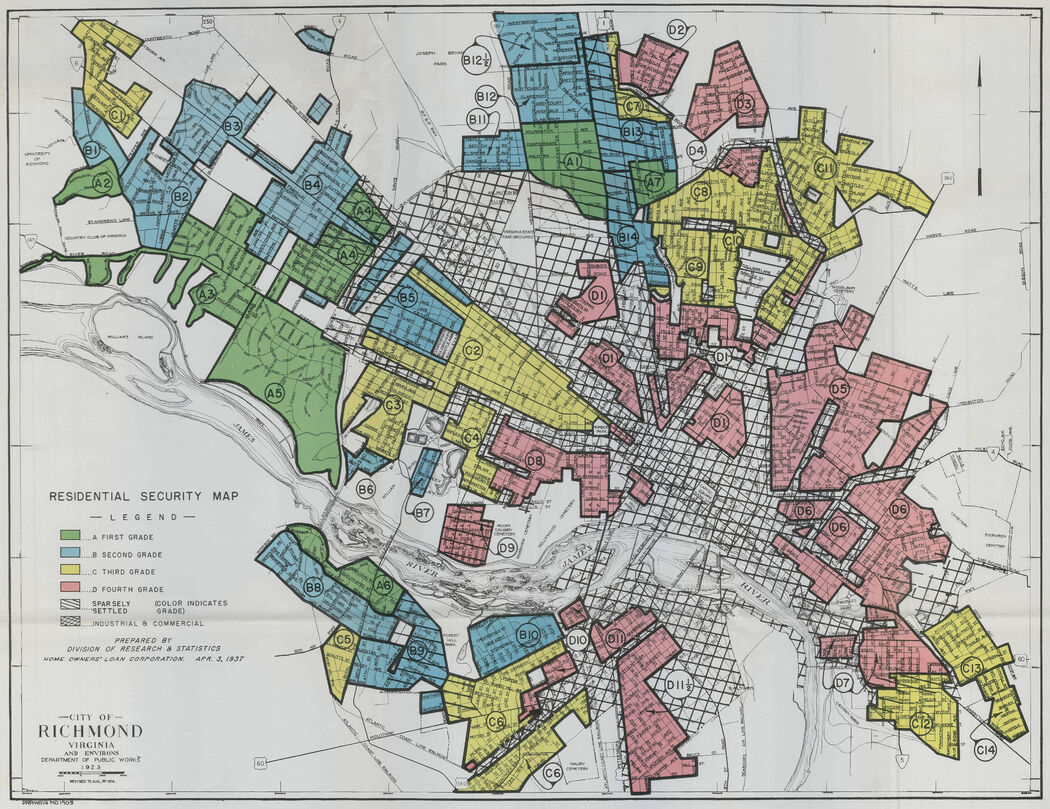

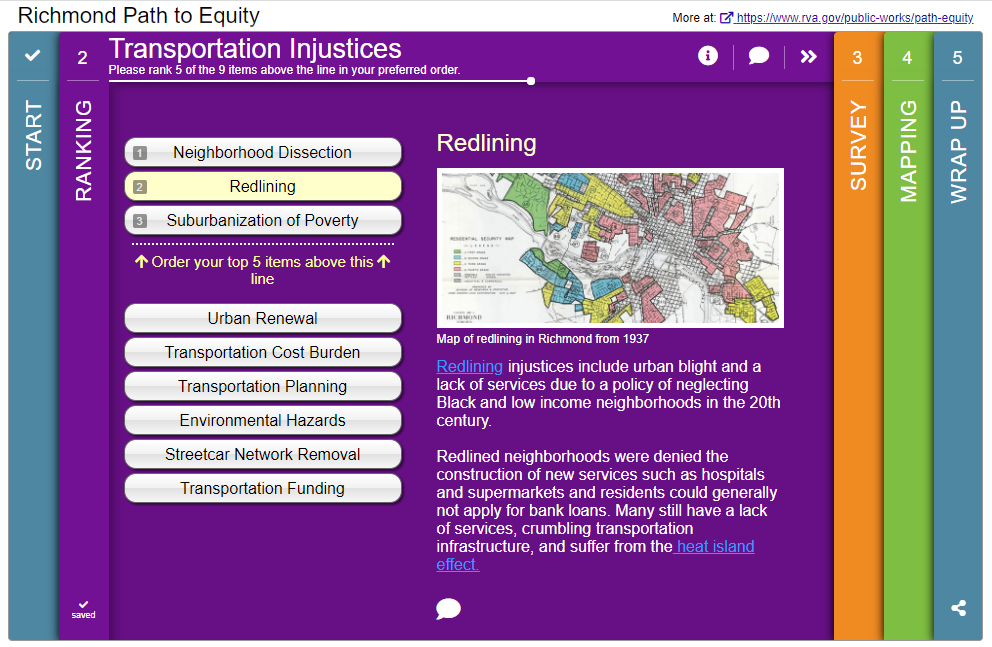

The legacy of redlining in Richmond helped to create a massive wealth gap between white and BIPOC citizens in the city.

The process greatly devalued land owned by BIPOC and low-income people and allowed the City to later purchase the land at low costs and concentrate the residents into affordable housing built on their demolished neighborhoods. Redlining also contributed to urban renewal and neighborhood dissection injustices. The following is a history of the injustice of redlining in the City of Richmond.

In the mid-1930s as part of the New Deal, the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC) began mapping cities based on how risky a mortgage loan would be for the government.

In almost all cases, BIPOC and low-income neighborhoods were labeled as a hazardous risk and colored in red on the map. This practice is now known as redlining.14 Redlined neighborhoods were cut off from essential Depression- era funding. This led to decline in housing condition and decreased property values. The HOLC redlined most of Richmond’s inner core, including the prosperous majority- Black Jackson Ward neighborhood.

In 1937, U.S. Congress passed a new housing act (Housing Act of 1937) which gave cities the power to establish public housing authorities to demolish “slums” and build public housing. Redlining had set the groundwork for what cities would define as slums – dense, BIPOC neighborhoods.

When Richmond City Council established the Richmond Redevelopment and Housing Authority (RRHA), its first major task was to acquire the land the city had devalued in northern Jackson Ward (a subarea called Apostle Town) by minimally compensating the residents, demolishing their neighborhood, and constructing a modernist public housing development – Gilpin Court (15).

While the scale of Apostle Town’s destruction was not matched for any other public housing project, most of the redlined areas in the City host a public housing development created by slum clearance. Redlined areas also have maintained a legacy of City neglect, most evident in crumbling transportation infrastructure and a significant lack of tree cover (16).

(14). “Timeline of Housing Events,” Virginia Memory, https://www.virginiamemory.com/online-exhibitions/exhibits/show/mapping-inequality/mapping-inequality-timeline

(15). Libby Germer, “A Public History of Public Housing: Richmond, Virginia,” Yale National Institute, https://teachers.yale.edu/curriculum/viewer/initiative_15.03.05_u.

(16). Brad Plumer and Nadja Popovich, “How Decades of Racist Housing Policy Left Neighborhoods Sweltering,” New York Times, August 24, 2020, https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/08/24/climate/racism-redlining-cities-global-warming.html

Richmond once had a comprehensive streetcar system that served much of the city. If the streetcar system existed today, it would provide access to several BIPOC and low-income neighborhoods in the East End, Northside, and Southside.

The injustice of removing the streetcar is not as clear cut as the other injustices. This injustice relates to “what could have been” more than “what once was.” Today, streetcars are a highly desirable amenity that typically see higher ridership numbers than a bus running on the same route. Benefits of the streetcar include: more walkable neighborhoods due to the increased distance a rider is likely to travel to high capacity transit; better air quality due to decreased car trips by use of an electric streetcar; increased commercial activity due to speculation over the streetcar’s ability to bring customers; decreased need for parking lots and thus the preservation of existing buildings due to the high-capacity nature of the streetcar; improved jobs access when combined with increased development; and increased housing construction due to the transit asset (17). It is possible that BIPOC and low- income residents could have benefited from the streetcar remaining. Unfortunately, due to the highly competitive nature of funding for streetcar projects, it is unlikely the City will ever see a system this comprehensive until federal funding priorities shift away from the automobile.

In 1887, engineer Frank Julian Sprague entered a contract with the City to implement an electric transit system. By 1888, Richmond had the first electric streetcar system in the world, leading to 110 streetcar systems under construction worldwide. The system peaked by the 1930s with 82 miles of track, enabling the rapid development of inner ring suburbs (18)

The system was immediately popular but remained segregated through its history. By 1904, armed motormen were enforcing this segregation with the threat of violence.

This set off a boycott of the system by Black Richmonders. This, combined with existing financial troubles from a motormen strike in 1903, led to the streetcar’s bankruptcy. The streetcar emerged from bankruptcy as the Virginia Railway & Power Company, the predecessor to Dominion Power. Segregation remained in place, but as a result of the boycott and bankruptcy, was not heavily enforced (19).

By the end of WWII, the public had come to see buses as a luxurious and modern alternative to aging streetcars. General Motors purchased Richmond’s streetcar system, along with systems in 45 other cities. General Motors destroyed the streetcar system and replaced it with gasoline- powered buses (20).

(17) Goody Clancy, “District of Columbia Streetcar Land Use Study: Phase One,” District of Coumbia Office of Planning, January, 2012, https://planning.dc.gov/sites/default/files/dc/sites/op/publication/attachments/FINAL%2520for%2520Web_Screen%2520View.pdf

(18) Harry Kollatz Jr., “Richmond’s Moving First,” Richmond Magazine, May 4, 2004, https://richmondmagazine.com/news/richmond-history/richmond-trolley-system/.

(19) Jack Eisen, “Boycott in Richmond,” The Washington Post, September 9, 1986, https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/local/1986/09/09/boycott-in-richmond/2dedf3c9-a70c-4f77-b900-3a6dcee46b7c/.

(20) Harry Kollatz Jr., “Richmond’s Moving First.”

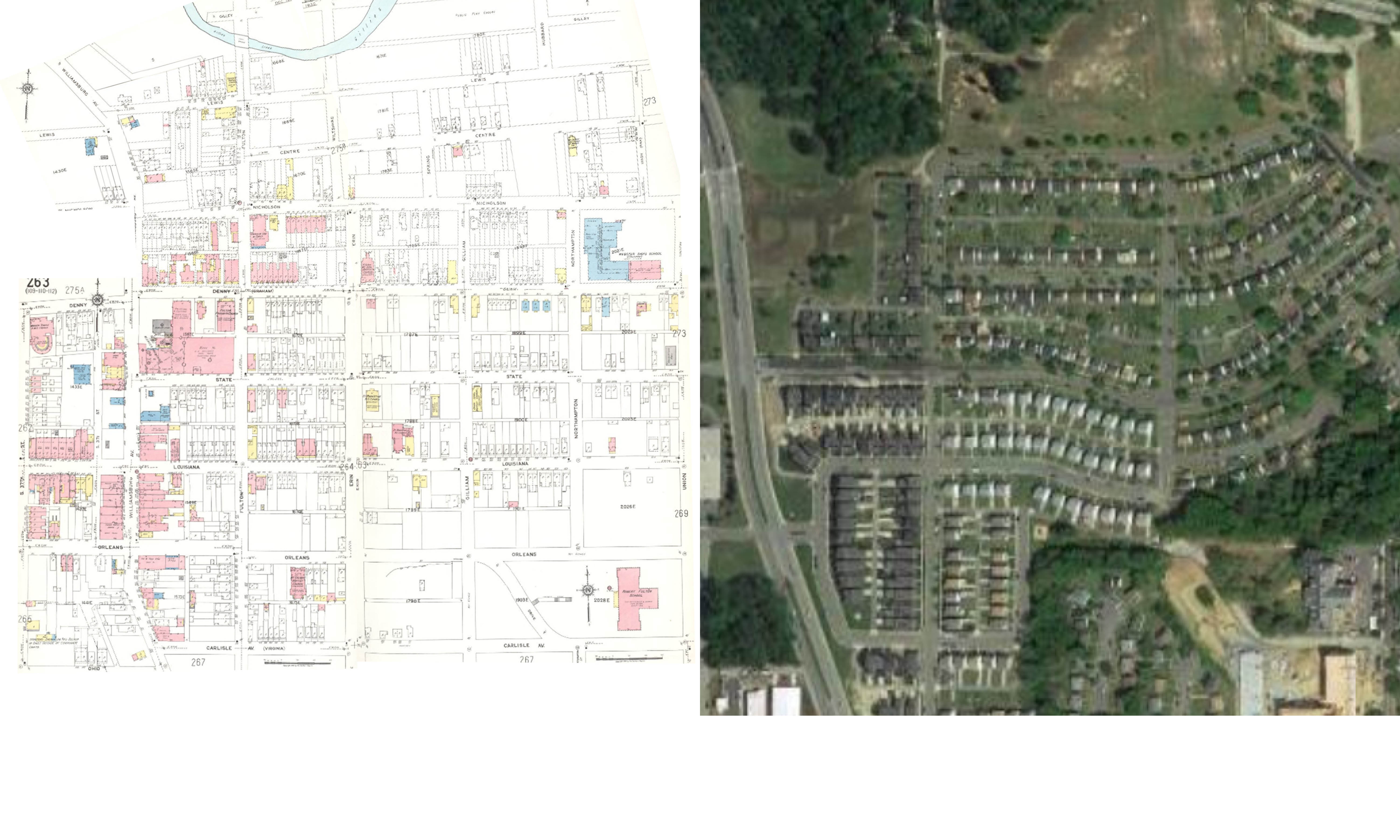

Urban renewal policies destroyed much of Black-owned Richmond. The practice entirely demolished Fulton Bottom and Navy Hill and demolished more than half of Randolph. Through urban renewal, Richmond has forever lost centers of Black culture and significant coverage of dense, walkable urban development. Urban renewal is strongly connected to redlining, and suburbanization of poverty injustices. The following is a history of the injustice of urban renewal in the City of Richmond.

Source: Richmond Times Dispatch

In 1949 as part of President Truman’s Fair Deal, Congress passed a new housing act (the Housing Act of 1949). This act provided additional funding for slum clearance, like the Housing Act of 1937, but cities no longer had to build public housing in place of the demolished slums.

Having already defined the slums, the City continued to demolish Black neighborhoods. With the ability to use eminent domain without replacing the demolished housing, RRHA had demolished over 4,700 units by 1959 and constructed back only 1,736 units of public housing (21).

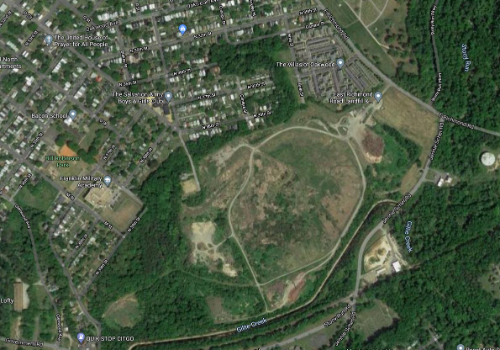

Large scale urban renewal projects in Richmond began in the Navy Hill neighborhood. Generally bounded by E. Broad Street, N 3rd Street, E Duval Street, and N 10th Street, Navy Hill was a dense Black neighborhood not dissimilar to adjacent Jackson Ward. The City began taking blocks of the neighborhood in the 1950s with the Public Safety Building. Government buildings and parking lots to support them continued to take block after block of Navy Hill through the 1960s. By 1970, the City constructed the Coliseum on four blocks of Navy Hill. In 1971, a new City Hall was constructed on one block of Navy Hill.

The Housing Act of 1949 stopped funding slum clearance by 1974, but the City continued these practices in Navy Hill (22). In 1981, J Sargeant Reynolds Community College took one block of Navy Hill. In 1985, the Sixth Street Marketplace opened in Navy Hill, partially using the historic Blues Armory. In 1986, what would become the Greater Richmond Convention Center was constructed on multiple blocks of Navy Hill. After the start of construction of the BioTechnology Research Park in 1992, only a handful of buildings from the original neighborhood remained.

In 1970 the City released the Fulton Urban Renewal Plan, targeting Fulton Bottom. The Fulton Bottom neighborhood was a Black, densely built, walkable, mixed-use neighborhood.

The City asserted that the buildings were in poor condition and could not be rehabilitated. The plan initially sought to replace all of Fulton Bottom with industrial uses, but to gain City Council support, RRHA incorporated affordable housing and community amenities for existing residents. Council approved the plan and HUD awarded the City funding to clear the neighborhood. By 1974, the neighborhood was entirely demolished.

While the plan originally incorporated amenities, commercial development, and programs to foster Black ownership of the land, these were amended out of the plan.

Over forty-five years passed before RRHA completed building the new Fulton Bottom as residential-only, suburban style development (23).

In their last action of HUD-funded neighborhood clearance, RRHA submitted the Randolph Urban Renewal Area Plan. While not as dense as Fulton and Navy Hill, Randolph was a walkable, mixed-use Black neighborhood. The plan would clear 1,600 housing units after the northern-most blocks had been demolished for the Downtown Expressway. Today, much of the rebuilt neighborhood is suburban in form and siting (24).

(21) Benjamin Campbell, “Richmond’s Unhealed History,” University of Richmond Digital Memory, https://blog.richmond.edu/digitalmemory/files/2016/08/Campbell_Richmonds-Unhealed-History.pdf

(22) “Slum Clearance in the United States,” Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Slum_clearance_in_the_United_States

(23) Catherine Komp, “Indelible Roots: Historic Fulton and Urban Renewal,” VPM News, July 21, 2016, https://vpm.org/news/articles/2402/indelible-roots-historic-fulton-and-urban-renewal.

(24) Department of Housing and Urban Development, “Randolph Urban Renewal Project Draft Environmental Statement,” HathiTrust, March 21, 1973, https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=ien.35556030636724&view=1up&seq=31.

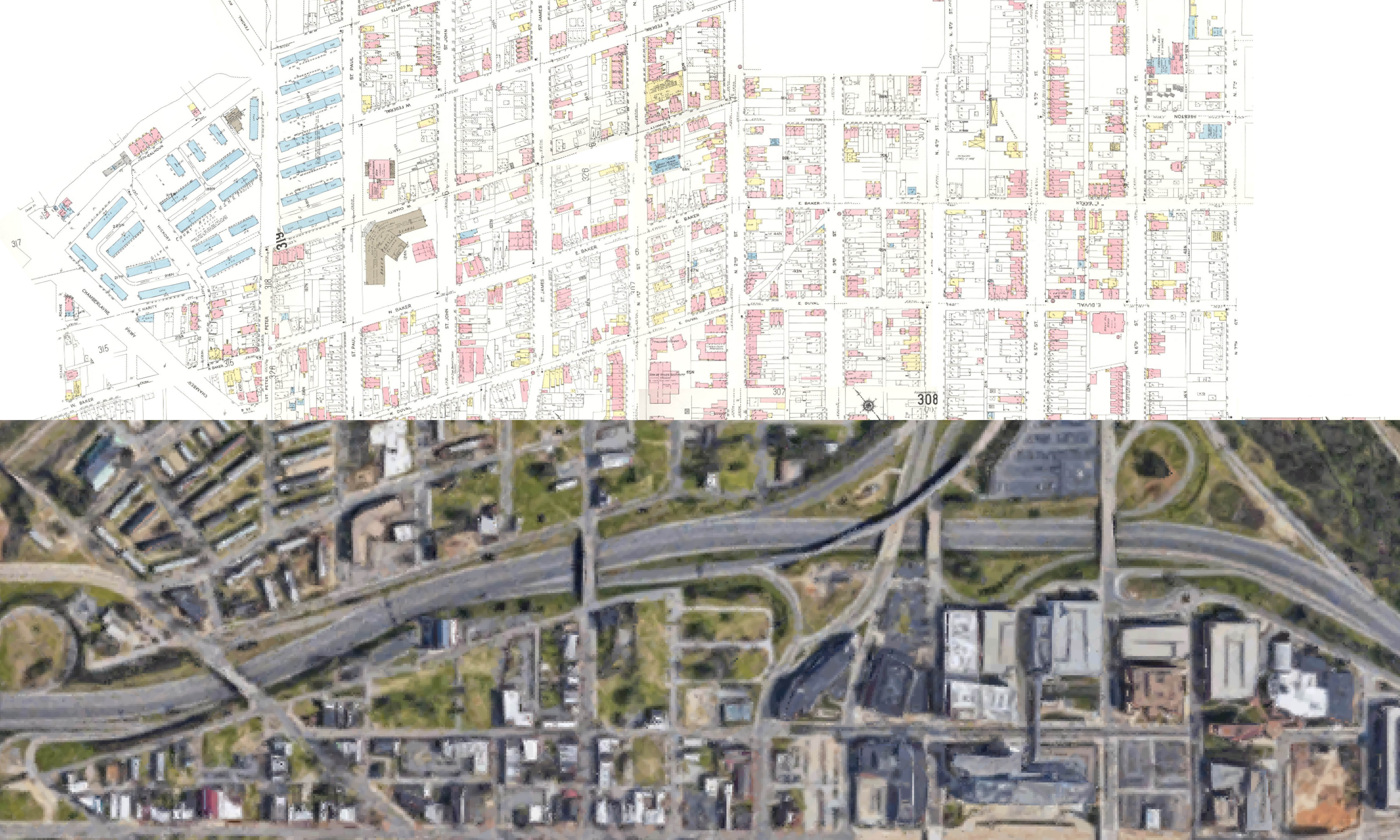

Neighborhood dissection has contributed to the permanent separation of many BIPOC and low-income neighborhoods from the wealthier, whiter urban core of Richmond.

Likely starting with redlining’s devaluation of BIPOC- and low- income-owned properties and their subsequent decay, the expanding highway and interstate system targeted these neighborhoods for total destruction. Neighborhood dissection is strongly connected to the urban renewal, suburbanization of poverty, transportation cost burden, and environmental hazard injustices. The following is a history of the injustice of neighborhood dissection in the City of Richmond.

The City invited renowned urban planner Harland Bartholomew to create a comprehensive plan for Richmond just after the close of WWII. Bartholomew’s plan proposed a city of walkable neighborhoods with schools and parks at their centers, but only for wealthier whites. This plan proposed removal, displacement, and destruction for city-designated slums and constructing highways in their place (25).

Meanwhile, the U.S. became entangled in the Cold War and the Eisenhower administration became fixated on the concept of mobilization. Mobilization is the act of quickly deploying troops and supplies through a network of connected infrastructure. By 1956, U.S. Congress passed the Federal- Aid Highway Act (FAHA), which resulted in the construction of the interstate system that has irreparably dissected most American cities.

Automobile use was on the rise in America and White Flight (detailed later in this chapter) commuters were burdening the existing road network in Richmond. With the streetcar removed by 1949, the region was quickly becoming car- dependent.

Richmond had begun construction of the Richmond-Petersburg Turnpike prior to the passing of the FAHA. In 1954, after twice failing to get public support to construct the turnpike through the heart of Jackson Ward and Shockoe Bottom, Richmond City Council created a special authority – the Richmond-Petersburg Turnpike Authority – to move forward with the highway by using state-sanctioned eminent domain powers (26). The highway took several blocks of Carver, Jackson Ward, Navy Hill and Shockoe Bottom. Before completion, it was incorporated into the interstate system under FAHA as I-95.

Richmond City Council used this same process again with the creation of the Richmond Metropolitan Authority (RMA), which used its state-sanctioned eminent domain powers to demolish a block-wide strip through the neighborhoods of Carytown (between Grayland Avenue and Idlewood Avenue), Byrd Park (between Parkwood Avenue and Idlewood Avenue), Randolph (between Parkwood Avenue and Grayland Avenue), and Oregon Hill (between Cumberland Street and Idlewood Avenue) – all historically Black and/or low-income communities formerly adjacent to the affluent Fan District. This also started the process of the near-complete destruction of Randolph far beyond the highway’s path (27).

(25) Harry Kollatz Jr., “A Man With a Plan,” Richmond Magazine, September 29, 2019, https://richmondmagazine.com/news/sunday-story/a-man-with-a-plan/.

(26) Harry Kollatz Jr., “The Curve Around the Station,” Richmond Magazine, September 23, 2013, https://richmondmagazine.com/news/richmond-history/I-95-cross-into-Shockoe/

(27) Harry Kollatz Jr. and Tina Eshelman, “The Distressway,” Richmond Magazine, December 16, 2016, https://richmondmagazine.com/news/richmond-history/the-distressway/.

Environmental hazards can cause lasting health issues in urban areas. In Richmond, environmental hazards include the interstates that splice the city, rail yards and rail corridors, waste disposal areas, and heavy industry.

BIPOC and low- income communities are five times more likely to be exposed to air pollution and 3.6 times more likely to live near a hazardous waste site (called a Superfund site) (28). Ambient fine particulate matter air pollution (PM2.5), which causes 85,000 – 200,000 deaths a year in the U.S., impacts BIPOC and low- income communities at a significantly higher rate (29). Where white people experience about 17% less air pollution than they produce, Black and Hispanic people experience 56% and 63% more air pollution than they produce, respectively (30).

Beyond pollution, BIPOC and low-income communities also bear the brunt of natural disaster impacts, especially urban flooding events (31). In Richmond, areas impacted by high pollution include most BIPOC and low-income neighborhoods. Environmental hazards are strongly tied to redlining, transportation funding, and transportation planning injustices. The following is an overview of environmental hazards and environmental justice.

Land uses that negatively impact air, land, and water quality are disproportionately adjacent to BIPOC and low-income communities (32).Researchers have observed an international trend where the eastern ends of cities are often low-income communities.

The leading theory on this concept is that westerly winds, which blow to the east, cause decreased air quality east of the center of the city, ultimately decreasing property values in those areas. Richmond is not spared from this phenomenon as some of its poorest communities are in the East End. Beyond this wind-carried pollution, the construction of low-income communities around polluting land uses is common due to the devalued land. This clustering would eventually lead to massive destruction caused by highway construction which targeted the lowest- valued land for acquisition (described in detail in the Neighborhood Dissection injustice). After construction, these highways and interstates would further deteriorate the air quality for the remaining residents. These high- pollution neighborhoods are typically in formerly redlined neighborhoods. As noted in the Redlining injustice, redlined neighborhoods today have minimal tree cover. Trees are essential to capturing air pollution and providing protection from dangerously high summer temperatures.

The suburbanization of poverty has likely pushed low-income residents to live in the lower cost housing adjacent to environmental hazards. Many of these communities are safe from flooding and have sufficient tree cover. However, the automobile-oriented lifestyle that is required to live in these areas brings with it increased automobile emissions. Moving and idling vehicles emit deadly PM2.5 pollution.

Environmental justice (EJ) is the concept that traditionally marginalized communities should not bear a disproportionate burden of environmental hazards.

President Clinton issued an executive order on environmental justice in 1994, which codified the term. Today, the Environmental Planning Agency (EPA) runs the EJ program at the federal level and monitors EJ programs at the state level. The Virginia Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ) runs the EJ program in the Commonwealth. The DEQ defines EJ as:

“Environmental justice is the fair treatment and meaningful involvement of all people – regardless of race, color, national origin or income – with respect to the development, implementation and enforcement of environmental laws, regulations and policies. No group should bear a disproportionate share of negative environmental impacts resulting from industrial, governmental and commercial operations or policies.” (33).

(28). The Green Initiative Fund, “Virginia,” Mapping for Environmental Justice, https://mappingforej.berkeley.edu/virginia/.

(29). Christopher W. Tessium, et al., “PM2.5 polluters disproportionately and systemically affect people of color in the United States,” Science Advances, April 28, 2021, https://www.science.org/doi/pdf/10.1126/sciadv.abf4491

(30). Jonathan Lambert, “Study Finds Racial Gap Between Who Causes Air Pollution And Who Breathes It,” NPR, March 11, 2019, https://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2019/03/11/702348935/study-finds-racial-gap-between-who-causes-air-pollution-and-who-breathes-it

(31). Thomas Frank, “Flooding Disproportionately Harms Black Neighborhoods,” Scientific American, June 2, 2020, https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/flooding-disproportionately-harms-black-neighborhoods/

(32). Center for Sustainable Systems, “Environmental Justice Factsheet,” University of Michigan, 2021, https://css.umich.edu/factsheets/environmental-justice-factsheet

(33). “Environmental Justice,” Virginia Department of Environmental Quality, https://www.deq.virginia.gov/our-programs/environmental-justice

The suburbanization of poverty is the culmination of several policies and demographic shifts.

The first shift was the rapid construction of the suburbs which greatly increased a form of housing that is disconnected from everyday needs and transit, requiring an automobile to access them. The second shift was the ongoing practices of slum clearance that destroyed more Black and low-income housing than it built back. The third shift was and continues to be the subsequent movement of impoverished residents into these suburban areas as they aged into affordability. The suburbanization of poverty is strongly connected to redlining, urban renewal, neighborhood dissection, and transportation cost burden injustices.

By the end of WWII, Richmond had a well-established inner ring of suburbs supported by the streetcar. These sorts of neighborhoods, called streetcar suburbs, enabled car-free lives for their residents and had a light mix of uses manifesting as commercial corridors. This streetcar network would be eliminated just four years after the war as Americans became infatuated with car ownership. This, combined with the GI Bill that made home ownership a reality for returning service people, resulted in a massive wave of suburban development. These new neighborhoods rigidly separated residential from commercial, making the car essential to travel for everyday tasks. Many of these neighborhoods also had restrictive ownership rules that prevented BIPOC residents from purchasing a home.

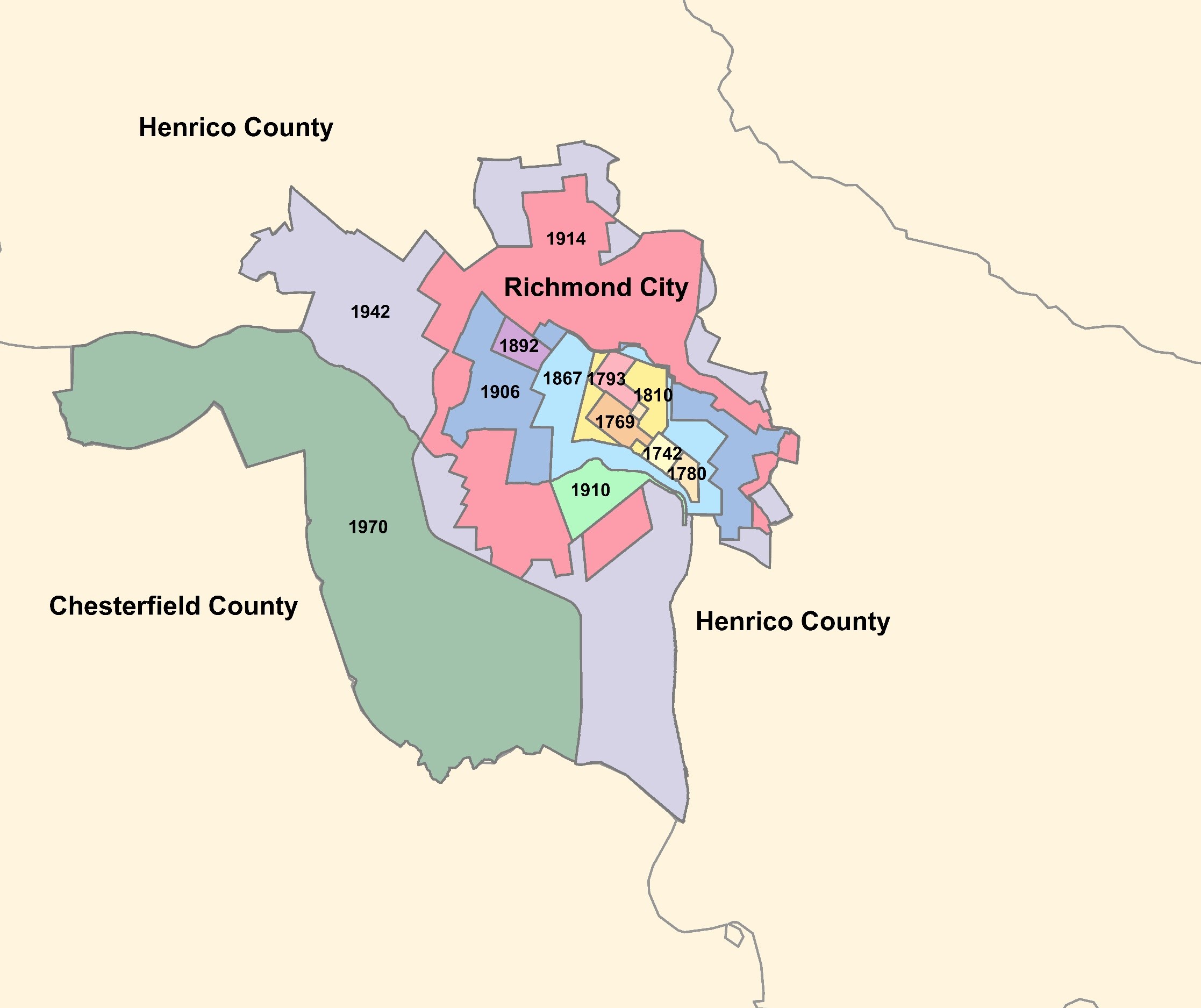

These conditions resulted in a significant abandonment of the inner city by wealthier whites, an era known as white flight. Richmond lost around 10,000 residents a year every year between 1950 and 1959 and continued to decline in population (not including the 1970 annexation) until the 2010 Decennial Census (34). This hemorrhaging of white citizens resulted in Richmond becoming a majority-Black city by 1970. City Council at that time was entirely at-large, meaning that its members were elected to represent the whole city instead of particular districts. This gave Black residents the potential to elect more favorable city representatives. This prompted the majority white city council to annex parts of North Chesterfield, reestablishing a white majority. In that same year, the Supreme Court ruled that this annexation was racially motivated and ruled that no local elections could take place until the City created a system of voting districts or wards. Council refused and no local elections were held until 1977 (35).

RRHA built its last additional unit of public housing by 1970 as part of a slum clearance project in Blackwell (36). All units constructed thereafter would be replacements for existing units. By the mid-1970s Apostle Town, Randolph, Navy Hill, and Fulton Bottom had been mostly demolished. Byrd Park, Oregon Hill, Carver, Jackson Ward, Shockoe Bottom, and Blackwell had lost several blocks of housing. RRHA, like most public housing authorities in America, had not provided a one-for-one replacement of lost units.

The loss of housing stock drove BIPOC and low-income residents to the edges of the city and beyond – moving into the now aging mid-century homes built twenty to thirty years earlier.

These residents found themselves living the car-dependent lives that the suburban developers had envisioned for much wealthier whites in the past. By the mid-2010s, white flight had reversed with a renewed interest in urban living. Today, the suburban areas of the region are far poorer than Richmond’s urban core (37).

(34) Amy Howard and Thad Williamson, “Reframing public housing in Richmond, Virginia: Segregation, resident resistance and the future of redevelopment.”

(35) Rich Griset, “Fifty years ago, Richmond took over part of Chesterfield. ‘The Politics of Annexation’ explores why,” Chesterfield Observer, April 28, 2020, https://www.chesterfieldobserver.com/articles/fifty-years-ago-richmond-took-over-part-of-chesterfield-the-politics-of-annexation-explores-why/.

(36) “Public housing in Richmond,” Church Hill People’s News, August 23, 2009, https://chpn.net/2009/08/23/public-housing-in-the-east-end/.

(37) Katie Demeria, “Povery growth in Richmond suburbs continues to outpace city’s,” Richmond Times-Dispatch, March 10, 2017, https://richmond.com/news/local/article_e9b1d2a3-9bfb-5c53-82e6-d0abb1c64699.html

Transportation cost burden is a modern issue that stems from the increasing dominance of automobile usage. The governmental prioritization of subsidizing road construction, expansion, and maintenance over transit, bicycle, and pedestrian subsidies has left most Richmonders car-dependent. BIPOC Richmonders are more likely to be low-income and therefore have a significant portion of their income go towards owning and operating a vehicle. This section expands on the concept of transportation cost burden in the City of Richmond.

In 2019, over a quarter of households in the Richmond region had more than three vehicles (38). Employment centers are scattered throughout the region with high density job areas extending as far as the Route 288/I-295 beltway. The Richmond region ranks 92 out of the 100 largest metropolitan areas in terms of transit access to jobs, with just 20.8% of workers having access to transit (39).

These conditions make car ownership essential in Richmond and greatly limit access to opportunity for the 17% of households that do not have a car at all.

As explained in the Suburbanization of Poverty injustice section, lower income people have been pushed to the suburban areas of the city and neighboring counties. These areas have limited or no transit options and are not built in a walkable pattern.

While the nationwide average household spends only 13% of their income on transportation, populations earning the lowest 20% (an average of just under $12,000 annually) spend almost a third of their income on transportation (40).

Vehicle ownership has set costs like registration, insurance, maintenance, and gas that do not scale proportionally with income. Low-income people are also more likely to purchase older or less reliable vehicles that may require more maintenance than pricier models.

The lack of viable alternative modes including regional transit, a connected bicycle network, and a full-coverage pedestrian network creates a heavy reliance for Richmonders of all incomes on private vehicles to get to their jobs, to shop, to see family and friends, and/or to access recreation. All public housing developments in Richmond and many low-income neighborhoods are connected to the local transit network. However, the headway frequency, number of transfers to reach a destination, and the limited coverage of the transit network can create significantly longer trips by transit. Efforts to decrease car-dependence should not assume that the transit-dependent have a high tolerance for long commutes.

(38) “The 12 Metro Areas That Are the Most Revved Up About Cars,” Wikilawn, https://www.wikilawn.com/blog/the-12-metro-areas-that-are-the-most-revved-up-about-cars/

(39) Amanda Merck, “City Leader Uses ‘Omnibus’ to Power Up Transit and Walkability in Richmond, Virginia,” Salud America!, February 10, 2020, https://salud-america.org/city-leader-uses-omnibus-to-power-up-transit-and-walkability-in-richmond-virginia/

(40) “The High Cost of Transportation in the United States,” Institute for Transportation & Development Policy, May 23, 2019, https://www.itdp.org/2019/05/23/high-cost-transportation-united-states/.

Insufficient and inequitable transportation funding is an overarching injustice connected to most of the injustices listed previously. Transportation funding as an injustice includes the federal and state policies that allocate funds. One example is the federal government offering cities millions of dollars to demolish neighborhoods in the past.

Cities and their neighborhoods are greatly impacted by funding priorities. If Richmond were to have a citizen-backed goal to accomplish a massive project, like reconstructing the streetcar network, the City would find funding for this undertaking extremely competitive. This is because the federal and state governments do not have a funding priority to construct massive streetcar systems. If the City desires to widen a highway, it would find that funding would be much easier to acquire. While these are just examples, they serve to illustrate the difficulties Richmond will face as it works to address these injustices.

Transportation planning as an injustice incorporates all other injustices noted before. Inequities today were not an accident – they are the result of intentional action or intentional inaction. Most of the federal policies that empowered transportation to be used as a means of neighborhood destruction or community displacement have been eliminated over time, but transportation planning today is not typically focused on healing the wounds caused by mid-century development.

In Virginia and most of the nation, transportation planning is centered on the automobile. Even Virginia’s dense urban areas place a heightened importance on preserving system capacity and vehicle speed.

Today, this aspect of transportation planning has become deadly. From 2008 – 2018, pedestrian deaths increased by 53% in the U.S., increased 63% in Virginia, and increased 250% in the City of Richmond (41). In 2017, Richmond’s pedestrian death rate was 4.93, meaning that for every 100,000 people total, 4.93 pedestrians were killed that year. In this same year, Virginia’s rate was 1.38. New York City – arguably the most walkable city in America – had a pedestrian death rate of 1.18 in 2017 (42).

Unfortunately, in 2020 the U.S. saw the highest one-year jump in pedestrian deaths since the 1970s (43). This peak is the result of several pandemic-specific conditions but highlights the failures of our pedestrian network.

Pedestrian death increases are directly tied to the suburbanization of poverty as more BIPOC and low-income people with limited car access move into suburban developments that have not incorporated safe walking and cycling infrastructure (44).

Path to Equity is the City’s first step in addressing the injustices described in this chapter. As the foundation of its forthcoming transportation plan, Richmond Connects, the City is poised to meaningfully address these injustices and provide a higher quality of life for Richmonders through equitable transportation.

(41) Wayne Covil, “Richmond group pushes for change as pedestrian death rate climbs,” WTVR, November 19, 2019, https://www.wtvr.com/2019/11/19/road-traffic-victims-event/

(42) Ali Rocket, “There were more pedestrian fatalities in Richmond last year than in any other year on record. This is why.,” Richmond Times-Dispatch, March 17, 2018, https://richmond.com/news/local/crime/there-were-more-pedestrian-fatalities-in-richmond-last-year-than-in-any-other-year-on/article_66b5ba24-82c6-5400-8512-5d0aa083e977.html

(43) Chris Teale, “Pedestrian deaths had largest year-on-year increase in 2020: GHSA,” Industry Dive, March 23, 2021, Smart https://www.smartcitiesdive.com/news/pedestrian-deaths-had-largest-year-on-year-increase-in-2020-ghsa/597140/.

(44) Wyatt Gordon, “What’s behind Virginia’s increasing pedestrian death toll and how to reverse the trend,” Virginia Mercury, October 27, 2020, https://www.virginiamercury.com/2020/10/27/whats-behind-virginias-increasing-pedestrian-deaths-and-how-to-reverse-the-trend/.

The Path to Equity plan will serve as the basis of Richmond Connects – the City’s multimodal transportation plan.

Path to Equity and Richmond Connects will operate within the framework of existing plans and planning processes. This section will outline the local, regional, state, and federal contexts that will guide the development of these transportation plans. Some existing plans and practices are helpful for implementing an equitable transportation framework, but some may slow or even hinder progress on equitable transportation as explained in the injustices of Transportation Planning and Transportation Funding.

COR’s current master plan is titled Richmond 300: A Guide for Growth.

City Council adopted the plan on December 14, 2020. The plan is guided by a city-wide vision that states:

“In 2037, Richmond is a welcoming, inclusive, diverse, innovative, sustainable, and equitable city of thriving neighborhoods, ensuring a high quality of life for all.”

Richmond 300 divides its goals and objectives into five topic visions: high-quality places, equitable transportation, diverse economy, inclusive housing, and thriving environment. Path to Equity and the forthcoming Richmond Connects plans will serve as implementation strategies for the “equitable transportation” topic vision. Richmond Connects is not a replacement for Richmond 300 and instead will be it’s detailed, data-driven transportation component.

RVAgreen 2050 is the City’s forthcoming equity-centered,

integrated climate action and resilience planning initiative.

This plan will serve as the implementation strategy of Richmond 300’s “thriving environment” topic vision. Led by the Office of Sustainability, RVAgreen 2050 will provide the framework for reducing greenhouse gas emissions 45% by 2030, with a plan to achieve net zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050. Path to Equity will incorporate the findings and recommendations of RVAgreen 2050 to accomplish the latter’s transportation-oriented goals and strategies.

The City adopted its Vision Zero Plan in 2017. The plan incorporates the Swedish Vision Zero initiative with the goal of reducing all traffic-related deaths to zero by 2030.

The plan is implementation-focused, including several actions and the departments responsible for completing said actions.

It is important to note that while BIPOC pedestrians are more likely to be struck and killed in the City of Richmond, addressing this and implementing Vision Zero must also be sensitive to the potential injustices that enforcement of traffic laws have on communities of concern, being careful to not trade one injustice for another.

Richmond’s Bicycle Master Plan is a 2014 document that provides an extensive full network of bicycle routes and infrastructure. Many of the plan’s recommendations have been implemented since its adoption.

Plans for the future of the city’s bicycle network will be developed and incorporated into Richmond Connects.

OETM is tasked with maintaining and expanding Richmond’s bike share program. Electric bicycles, or E-bikes, are already part of the system and have the potential to be a larger part of the stock. E-bikes could make cycling a more viable alternative to the automobile.

COR has many additional plans such as small area plans, trail plans, and park plans that provide specific recommendations for the growing city. Richmond Connects will incorporate all relevant and adopted plans.

Plans | Richmond (rva.gov)

Transportation inequities do not stop at the Richmond city line. The legacy of car-dependent suburban expansion and the continuing growth of poverty in the suburbs has decentralized employment and housing throughout the Richmond region, especially in the adjacent counties of Henrico and Chesterfield. Both Henrico and Chesterfield Counties have begun their own equity programs in their public schools and their governmental departments. These processes are an essential foundation to developing a more equitable future. The completion of the Path to Equity plan should serve as a model for further developing transportation equity considerations in the Richmond Region.

Annexation has played a significant role in preserving inequities in the Richmond-Henrico-Chesterfield area. Richmond’s most recent annexation in 1970 incorporated most of the Southside. The street network here was designed as car-oriented suburbs, leaving the City with ongoing challenges in maintenance and mobility improvements.

While this annexation has its own unique restrictions, the inability to further annex also causes challenges to improving transportation equity. Since 1984, Virginia has had a moratorium on municipal annexations. Richmond is the region’s dense urban core and has a more extensive network of transportation infrastructure to maintain and improve. This puts more fiscal strain on the city, which is transferred to its residents as an increased tax burden when compared to surrounding suburban counties. This, in part, has led to continued growth in the counties due to much lower taxes. Because the City cannot annex any parts of these counties, its existing tax base must carry the full burden despite its transportation network being essential to people in the counties as well. The hard line created between the city and the counties also carries over into transportation planning where the counties continue to expand car dominance for the most part.

The following sections also detail the limitations to funding, planning, and programming that are inherent in the laws and regulations of each entity involved in transportation decision-making. The conversation the City is having to achieve equity in transportation cannot be accomplished in the current context.

As noted in the injustices section, transportation planning and transportation funding programs limit the way improvements can be made. The study team seeks to describe the policies that would need to change in order to achieve true equity in transportation.

Citizens of Richmond must advocate for regional, state, and federal legislation to address these shortfalls and rework how projects are funded and implemented to be successful in achieving transportation equity.

The Virginia General Assembly created the CVTA in 2020 to administer new funds within the PlanRVA boundary.

The CVTA collects an additional regional sales and use tax of 0.7% and a wholesale gas tax of 7.6 cents per gallon of gasoline and 7.7 cents per gallon of diesel (45). Half of the CVTA’s revenue will be returned proportionally to the jurisdictions, 35% will be dispersed at the discretion of the CVTA board, and 15% will be provided to the Greater Richmond Transit Company (GRTC) (46). In August, COR used their CVTA funds to shrink a six-year backlog of sidewalk maintenance projects (47). This illustrates the flexibility of this new funding source.

(45) “Central Virginia Planning Authority,” PlanRVA, https://planrva.org/transportation/cvta/.

(46) Jim McConnell, “Regional group forms to fund road, transit goals,” Chesterfield Observer, August 4, 2020, https://www.chesterfieldobserver.com/articles/regional-group-forms-to-fund-road-transit-goals/.

(47) Chris Suarez, “Richmond to repair 8 miles of sidewalk over the next year for $2.4 million,” Richmond Times-Dispatch, August 6, 2021, https://richmond.com/news/article_1bd3459a-26ad-59e8-b7f8-7e67f66fae5c.html

GRTC is the regional transit provider. GRTC provides fixed route transit service in the City of Richmond and Henrico and Chesterfield Counties. GRTC’s demand responsive (paratransit) services CARE and CARE Plus are also available throughout the City of Richmond for qualified passengers. GRTC’s fixed route transit services operate seven days a week with a span of service as long as 5 AM to 1 AM on some routes. Since the beginning of the pandemic, GRTC has been operating fixed route services fare-free. A goal of OETM is to extend the life of this fare- free system.

GRTC is responsible for its own planning and public engagement. The transit provider is responsive to the needs of its customers and works closely with jurisdictions in the region to expand and improve the transit network. With the creation of a Director of Equitable Innovation and Legislative Policy position, GRTC is committing to cultivating and expanding a more equitable transit future.

Any of Richmond Connect’s proposed transit policies would have to be adopted by GRTC if they are to be implemented.

GRTC’s planning process is highly driven by involvement of its funding partners – the City and Counties served by GRTC establish their funding contributions, request service changes, collaborate on studies of network and facility changes, and specify the priorities for any changes or expansion to the system. Some changes precipitated by GRTC operational constraints such as availability of bus operators may be determined by GRTC but are guided by priorities defined by the GRTC board. The GRTC board is comprised of six members, three each appointed by the City of Richmond and Chesterfield County. The CVTA has undertaken a study with GRTC to evaluate GRTC’s management structure. The requirements of the CVTA and the outcome of this study may result in a revised structure.

The current and upcoming initiatives by GRTC include equity-based programs like free fares and bus stop enhancements. GRTC is also investigating microtransit - an on-demand service of smaller buses, vans, and shuttles.

The next major plan update by GRTC will transition from Transit Demand Planning to Transit Strategic Planning under state requirements; these requirements include establishing performance measures as a basis for service plans. These measures will be determined by the GRTC Board and could include equity measures if the City were to voice that priority in the planning process. Furthermore, the 2021 Virginia Assembly required DRPT to undertake a Transit Equity and Modernization study that is likely to provide new guidance on incorporating equity measures and practices in future planning. This overall direction aligns with Path to Equity, but since Path to Equity is ahead of changes in state guidance, there is an opportunity to shape transit planning practices in Richmond with the City’s approach to establishing equity factors and applying them to the prioritization of transportation needs.

GRTC is also improving bus stops across the network.

Their shelter installation plan extends into 2024 (48). This work is supplemented by RVA Rapid Transit, which collects donations for the Better Bus Stop program (49).

An important note is that GRTC is subject to Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. This requires GRTC to perform detailed studies if an action has the potential to harm based on race or ethnicity. For a system the size of GRTC, a 25%-change threshold will activate the Title VI process.

These changes include the total number of trips, the hours per day that buses run the route’s alignment, and the route’s length. Proposed eliminations of a route will also activate the Title VI process.50 This process is essential in protecting BIPOC and low-income mobility, but it can become a box- checking exercise for transit agencies as Title VI alone does not require the implementation of a more equitable system (51). GRTC completed a major system-wide redesign in 2018 after a thorough analysis backed by an intensive public engagement process. Going far beyond Title VI’s requirements, the redesign increased jobs access for low- income communities by 10% and should be a model for planning beyond the box-check (52).

(48) GRTC Shelter Plan FY20-FY24,” Greater Richmond Transit Company, https://ridegrtc.com/media/annual_reports/Shelter_Plan_Presentation_Board_Meeting_2_18_20.pdf

(49) Better Bus Stop Program, RVA Rapid Transit, https://www.rvarapidtransit.org/better-bus-stop

(50) “Major Change and Service Equity Analysis,” Greater Richmond Transit Company, October 11, 2017, https://www.ridegrtc.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/Summer-2018-Service-Changes.pdf

(51) “Inclusive Transit: Advancing Equity Through Improved Access & Opportunity,” TransitCenter, July 17, 2018, https://transitcenter.org/publication/inclusive-transit-advancing-equity-improved-access-opportunity/#

(52) Chris Suarez, “The firm that helped redesign GRTC bus routes last summer says critical VCU report is flawed,” Richmond Times-Dispatch, June 19, 2019, https://richmond.com/news/plus/article_cbd293e6-5d9d-5b88-badb-2e2bd7031afb.html

PlanRVA is a regional organization comprised of elected officials, staff, and citizen representatives from nine jurisdictions: the Town of Ashland, Charles City County, Chesterfield County, Goochland County, Hanover County, Henrico County, New Kent County, Powhatan County, and the City of Richmond.

Often referred to as a council of governments in other states, these organizations are called planning district commissions (PDC) in Virginia. All jurisdictions fall within a PDC boundary. Housed within PlanRVA is the Richmond Regional Transportation Organization (RRTPO). The RRTPO is a metropolitan planning organization (MPO), which are federally required to complete regional transportation plans and distribute funding from certain federal programs. RRTPO covers all of the Town of Ashland, Hanover County, Henrico County, and the City of Richmond. It covers portions of Charles City, County, Chesterfield County, Goochland County, New Kent County, and Powhatan County.

The adopted ConnectRVA 2045 is the regional Long Range Transportation Plan (LRTP).

An LRTP is federally mandated and covers a 20-year period. Regional planning brings independent jurisdictions together and focuses on regionally-significant projects. At this scale, projects that benefit multiple jurisdictions are often highway expansions and improvements. This condition creates a highly- competitive funding environment where targeted accessibility improvements may not perform well. RRTPO does administer other funding programs that focus on these projects like Transportation Alternatives (TA) and Congestion Mitigation and Air Quality (CMAQ). RRTPO’s Regional Surface Transportation Block Grant (STBG) also provides funding for local projects and includes maintenance, which is typically not funded by larger grant programs.

Of the five goals for the LRTP, one is an equity goal. The goal is defined with objectives to reduce trip lengths and increase access to activity centers via transit, walking, and cycling.

Because this plan exists at the regional level, this goal will focus on federally-designated EJ populations. RRTPO defines the region’s EJ populations (areas with large BIPOC, low-income, and limited English proficiency (LEP) populations) and Title

VI requirements in their Title VI Plan. RRTPO incorporates EJ populations into their “Equity and Accessibility” scoring process and completes an EJ analysis for the list of constrained projects after they are scored into the LRTP.

Virginia’s primary transportation funding stream is currently the SMART SCALE program administered by the Office of Intermodal Planning and Investment (OIPI). SMART SCALE uses an outcomes-based scoring system that aids in selecting which projects receive funding, with a heavy emphasis on projects that fulfill Virginia’s Transportation Plan’s (VTrans) needs. After the application, screening, and scoring processes, a successful project will receive funding within the following five years.

This process is an improvement to the schedule of funding prior to SMART SCALE where projects could be delayed for years.

SMART SCALE also has a wider scope than any statewide funding system prior, allowing a wide variety of transportation projects to apply. SMART SCALE has been met with mixed opinions from transportation professionals and from local governments. Aware of these critiques, OIPI frequently refines the SMART SCALE process to close gaps in fairness and to further streamline the process.

VTrans incorporates transit equity under Goal B: Accessible Places. This goal groups alternative transportation modes and industrial, economic, and urban growth areas. Transit equity falls under the objective “Transit Access for Equity Emphasis Areas,” which spatially identifies BIPOC, low-income, and Limited English Proficiency concentrations.

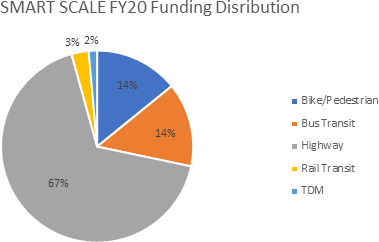

While SMART SCALE provides millions in funding for transit, bicycle and pedestrian, rail, and transportation demand management (TDM), the majority of funding goes to highway projects.

In their FY20 scoring round, SMART SCALE committed 67% of its available funds to highway projects(see Figure 19). These numbers reflect Virginia’s dependence on the automobile and have the potential to preserve that dependence for decades to come.

As described in the transportation injustices section, car-oriented transportation planning and funding can have a detrimental impact on BIPOC and low-income people.

A major challenge will be in shifting away from car culture and putting forward stronger multimodal projects for SMART SCALE funding.

SMART SCALE’s Accessibility factor measures the increase in access to jobs for disadvantaged communities. This analysis groups populations within a 45 minute drive and a 60 minute transit commute. Because of these large catchment areas, the accessibility measure is inherently regional and car-oriented. The separate Land Use factor assesses the increase in walkability but does not award higher scores for disadvantaged populations. For SMART SCALE, the applicant is expected to complete all the necessary federal requirements for EJ and Title VI if applicable. Incorporating the rigorous equity emphasis that Path to Equity will place on city transportation projects would not impede a project from finding success in the SMART SCALE scoring process. Rather, the incorporation of equity considerations for all transportation projects will not only advance the Richmond Equity Agenda, but also create more competitive projects. SMART SCALE submissions that comprehensively address transportation issues, especially with multimodal solutions, should score much higher than those that only address congestion and capacity.

VDOT administers several funding programs for transportation projects. These programs include the State of Good Repair (SGR) Program, the Highway Safety Improvement Program, and the Revenue Sharing Program. These programs fund smaller projects and system maintenance that are not covered by or unlikely to be competitive for SMART SCALE funding.

The Virginia Office of Transportation Research and Innovation requested the completion of a study on electric vehicles in 2020. The study acknowledges that BIPOC and low- income communities in Virginia receive a disproportionate level of exposure to deadly vehicle emissions. The report recommends that Virginia governments and transit companies switch to electric school buses, transit, and fleet vehicles to help eliminate tailpipe emissions in these communities. The report also recommends the installation of chargers in these communities to provide to them the option of owning an electric vehicle (53). When evaluating equitable implementation of electric vehicle charging stations, the Seattle Department of Transportation observed that law enforcement targeted BIPOC charging station users (54). When installing a network of charging stations, it is essential that these situations are eliminated.

(53) “Electric Vehicle Readiness Study,” Presentation, March 17, 2021, https://ctb.virginia.gov/media/ctb/agendas-and-meeting-minutes/2021/march/pres/ev_readiness_study_ctb_presentation_03-17-21_final.pdf

(54) “Electric Vehicle Charging in the Right-of-Way Permit Pilot,” Seattle Department of Transportation, https://www.seattle.gov/documents/Departments/SDOT/NewMobilityProgram/EVCROW_Evaluation_Report.pdf

The Department of Rail and Public Transit (DRPT) is VDOT’s sister agency for transit planning and funding. DRPT assists and monitors the dozens of transit companies and agencies throughout the Commonwealth.

Since 2018, DRPT has offered the Making Efficient + Responsible Investments in Transit (MERIT) program. The intent of the program is to bring additional accountability to transit providers and provide paths forward to better transit networks. The MERIT program essentially provides transit companies the assistance to complete a strategic plan that identifies the needs of their communities. Another major DRPT program is the Transit Ridership Incentive Program (TRIP). TRIP was created to improve regional transit service in large urban areas and to reduce barriers to access for low-income people. TRIP has two sub-programs: TRIP – Regional Connectivity and TRIP – Zero Fare and Low Income. GRTC is currently using a TRIP grant to provide zero fare rides and to study the feasibility of a zero fare system. While GRTC completes the study, the system is free to ride (55).

(55) “DRPT Awards $8M State Grant to GRTC to Study Zero Fares,” Greater Richmond Transit Company, December 21, 2021, https://www.ridegrtc.com/news-initiatives/press-releases/drpt-awards-8m-state-grant-to-grtc-to-study-zero-fares

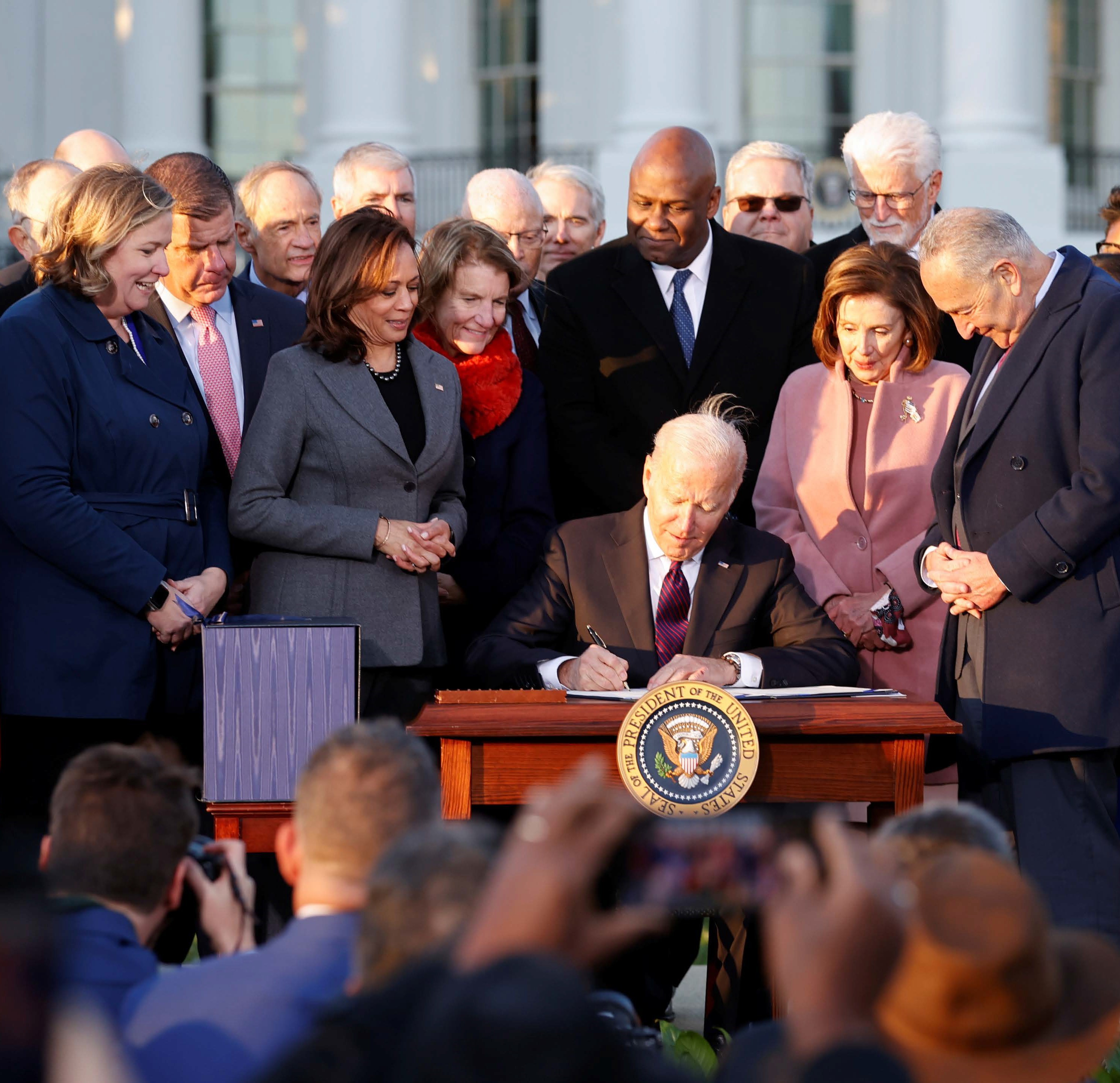

Two major pieces of federal legislation that impact transportation equity are Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the 1994 Executive Order (EO) 12898 titled “Federal Actions to Address Environmental Justice in Minority Populations and Low-Income Populations.” Title VI was addressed briefly in the prior discussion of GRTC. Title VI states:

No person in the United States shall, on the ground of race, color, or national origin, be excluded from participation in, be denied the benefits of, or be subjected to discrimination under any program or activity receiving Federal financial assistance.

Title VI dictates that the receiver of federal funding must comply with the Civil Rights Act of 1964. This typically manifests in impact analyses that require an investigation of benefits and adverse effects when planning a project that intersects with a community of concern. As mentioned in the GRTC discussion, one common example of Title VI in practice is when a transit provider, which almost certainly receives federal funding for their operations, seeks to redesign a transit system.

EO 12989 established environmental justice guidance. EJ considerations, like Title VI, are required when using federal funds. The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) provides oversight and additional guidance on committing to EJ. EPA defines EJ as:

The fair treatment and meaningful involvement of all people regardless of race, color, national origin, or income with respect to the development, implementation and enforcement of environmental laws, regulations and policies.