Kimberly Chen

kimberly.chen@rva.gov

(804) 646-6364

Alex Dandridge

Alex.Dandridge@rva.gov

(804) 646-6569

900 E. Broad St., Room 510

Richmond, VA 23219

Monday - Friday 8 a.m. - 5 p.m.

Historic Preservation

Staff are well versed in all aspects of historic preservation in Richmond and are responsible for administering the City's Old and Historic District Ordinance, providing staff support to the Commission of Architectural Review, and overseeing Section 106 review for projects in accordance with the City of Richmond Programmatic Agreement.

Planning staff administers an on-going process to identify eligible historic resources in Richmond. This process involves analysis of historic data, field work, mapping in GIS, and consultation with the Virginia Department of Historic Resources.

The primary purpose of this effort is to identify historic resources that must be taken into account as a part of the Section 106 process. The identification process also provides data on eligible historic resources that can be considered in the development of the Master Plan, neighborhood plans and zoning amendments.

The identification process also identifies historic resources that can be proposed for historic designation at the city, state, or federal level.

City Old and Historic Districts

National Register Historic Districts

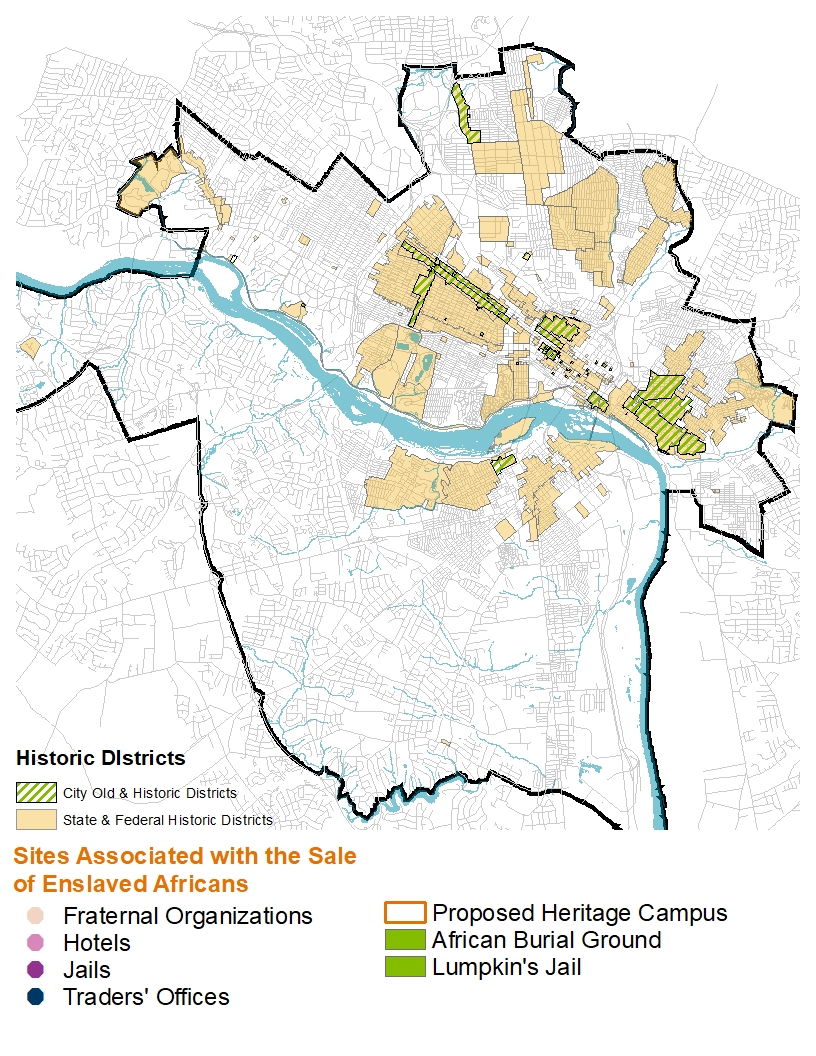

In Richmond, there are two forms of historic designation. The first and oldest form of designation is individual properties and districts identified as City of Richmond Old and Historic Districts. The second and larger group of designated historic resources consists of individual properties and districts concurrently listed on the Virginia Landmarks Register (state) and the National Register of Historic Places (federal). A property or district in Richmond can have all forms of historic designation.

In 1957, the St. John's Church Old and Historic District was created by Richmond City Council in response to citizen appeals to help preserve the character of the neighborhood surrounding historic St. John’s Church on Church Hill. As a result, the Commission of Architectural Review was established to administer and protect the St. John's Church Old and Historic District. Since that time, 15 additional multiple-property districts and a number of individual-property districts have been added to the Commission's jurisdiction, for a total of approximately 4,006 properties.

Planning and Preservation staff administer all steps in the designation of Old and Historic Districts. This designation process is governed by the requirements of the Richmond Zoning Ordinance Section 30-930 and procedures adopted by the Commission of Architectural Review. The creation of Old and Historic Districts is a community-driven process that originates with sponsors at the neighborhood level. The creation of an Old and Historic District is a zoning overlay process, and requires affirmative votes by the Commission of Architectural Review, Planning Commission, and City Council to establish a district.

The requirements of Old and Historic Districts and related documents are covered in depth on the webpage for the Commission of Architectural Review.

The Virginia Landmarks Register (VLR) and the National Register of Historic Places (NRHP) are official state and federal listings of districts and individual properties that exemplify the history and culture of Virginia and the United States. Richmond has been a national leader in the designation of historic resources, due in part to the ongoing support of nominations by the City of Richmond in general and Planning and Preservation Division in particular. In Richmond, there are over 154 individual properties and 122 historic districts, containing nearly 28,000 properties, listed on the VLR and NRHP.

The state and federal registers are administered by the Virginia Department of Historic Resources and the National Park Service. The role of Planning and Preservation staff in that process is supportive and includes: supplying city property data, providing technical assistance on historic research and boundary identification, and commenting on historic resources as a part of the Certified Local Government Program.

Listing on the NRHP and VLR is largely honorific, providing recognition of a property’s unique historical and architectural character. Property owners residing within NRHP and VLR districts or individually listed properties are not subject to any historic review requirements. Properties that have been determined to contribute to a designated district or are individually-designated are eligible for state and federal Historic Rehabilitation Tax Credits. The impact of state-funded development activities on state-designated historic resources is taken into account in the Virginia Environmental Review process. The impact of Federally-funded undertakings on historic resources is taken into account as a part of the Section 106 Review process. A map showing the location of VLR and NRHP designated resources can be viewed in ArcGIS. Information on specific properties in VLR and NRHP Historic Districts can be viewed in the GIS Parcel Mapper. Once you have selected the parcel you wish to view, click on the Planning Tab for information about the historic districts.

Planning staff addresses historic preservation issues in area specific plans, such as the Monroe Park Master Plan. Planning staff works to address historic resource and preservation issues in updates to existing planning documents, and assist preservation organizations such as Historic Richmond, Preservation Virginia, and the Virginia Department of Historic Resources in their planning efforts.

Section 106 of the National Historic Preservation Act (16 U.S.C. 470f) governs the review of federally-funded activities known as undertakings. Federal regulations 36 CFR Part 800, Protection of Historic Properties, implement Section 106 review and these regulations are summarized in A Citizen’s Guide to Section 106 Review.

The Planning and Preservation Division is responsible for reviewing undertakings within the corporate limits of the City of Richmond that receive Federal funds from the U. S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD). Undertakings reviewed include home repair, rehabilitation, new construction, and demolition that are related to HUD funding passed through the City of Richmond or provided directly to other agencies. These HUD-related reviews are completed under the terms of the Richmond Programmatic Agreement (PA):

Under the terms of the Programmatic Agreement some 200 to 400 undertakings are reviewed annually and for a number of these the Planning and Preservation staff consults with the Virginia State Historic Preservation Officer (SHPO), also known as the Virginia Department of Historic Resources. As a part of each review, a determination is made whether or not an undertaking will affect historic properties, which are listed individually or as districts that are eligible for the Virginia Landmark’s Register (VLR) or the National Register of Historic Places (NRHP). If historic properties are affected by an undertaking, Planning and Preservation staff will work to ensure that adverse effects to these historic properties are avoided or mitigated.

Many of these undertakings are a part of the Richmond Neighborhoods in Bloom program and are reviewed with the City Department of Housing and Community Development. The Division also provides comments and technical assistance for non-HUD funded undertakings in Richmond.

Information on recent Section 106 reviews are listed below:

The City compiles a list of all complete and active Section 106 projects on a monthly basis. Please click on the links below for additional information.

- 2020 Monthly Reports

- 2021 Monthly Reports

- 2022 01 January Monthly Report

- 2022 02 February Monthly Report

Questions and input on the Section 106 review process and particular undertakings are welcomed. Staff responsible for Section 106 review can be contacted by e-mailing Kimberly Chen at kimberly.chen@rva.gov, or by calling 804-646-6364.

Planning staff coordinates the comments of various departments of the City of Richmond on state Environmental Impact Reviews (EIRs) and provides specific comments on historic preservation issues. Planning staff provide comments on Special Use Permits, Plans of Development, and is a part of the PDR project review team.

City-Wide Historic Preservation Plan

Richmond 300 calls for the development and regular updating of a city-wide preservation plan to establish near and long-term preservation priorities and to identify proactive and innovative ways to protect the character, quality, and history of the city. In 2022, Richmond was awarded a Cost-Share Grant by the Virginia Department of Historic Resources to implement the first phase of this planning activity, which will include data gathering, analysis, and community outreach.

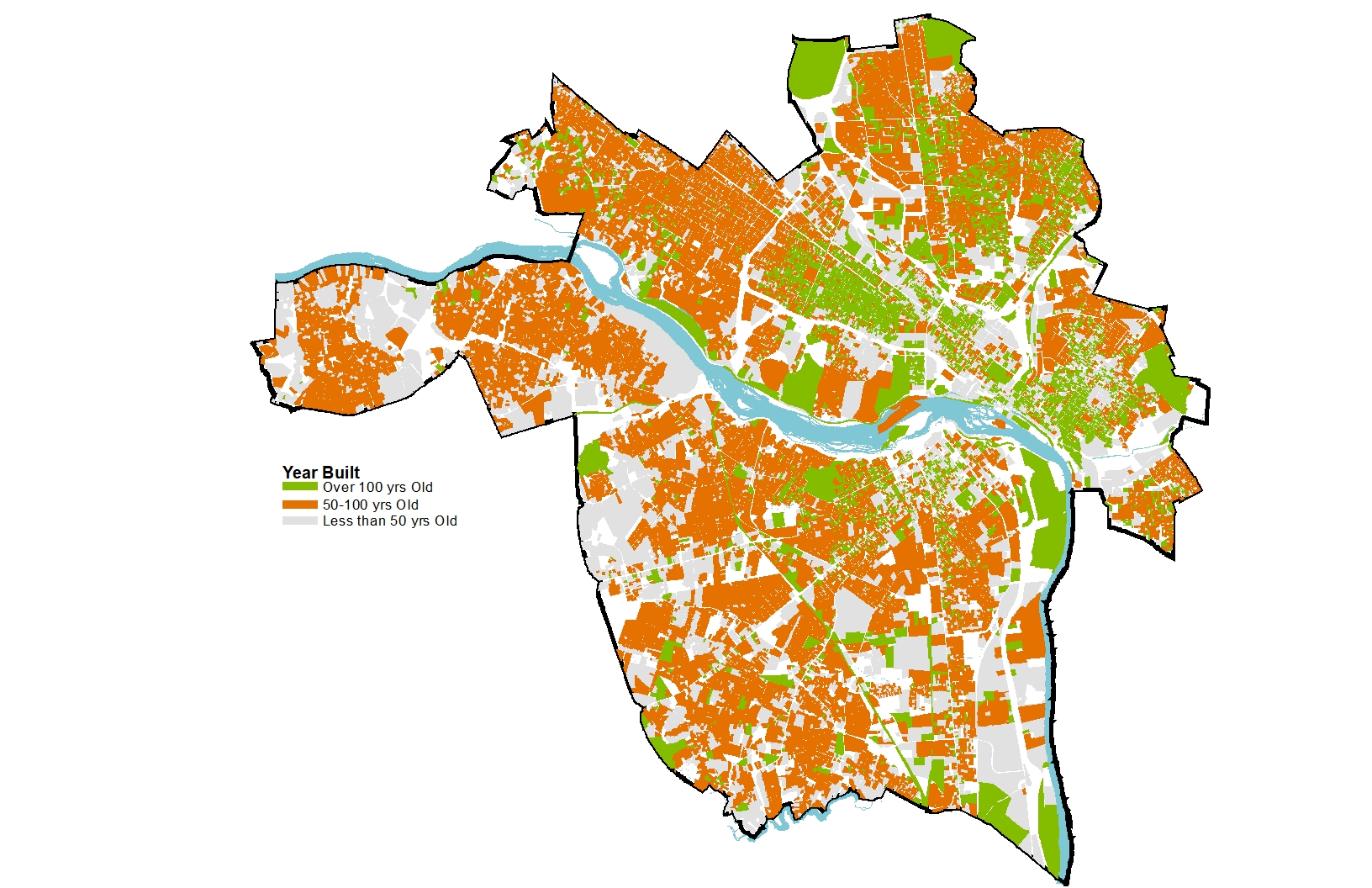

A city rich in history, Richmond was first laid out in 1737, established as a town in 1742, became the third capital of the Commonwealth of Virginia in 1779, and was incorporated as a city in 1782. Today, there are slightly over 68,000 buildings in Richmond, of which nearly 23% are over 100 years old, and 81% are at least 50 years old. Approximately 22,000 buildings in the City are listed on the Virginia Landmarks Register and/or the National Register of Historic Places. These designations are honorific and offer little to no protection. Although Richmond values history and historic neighborhoods, it has not previously established a comprehensive process for identifying, evaluating, and protecting historic buildings, neighborhoods, and landscapes, especially historically Black communities and cemeteries.

The purpose of the City-Wide Historic Preservation Plan will be to strengthen the City's existing preservation policies, ordinances, and programs through a long-term vision and the creation of practical policies and achievable goals for improving historic preservation within the City. The Historic Preservation Plan will build on past successes, such as compliance with federal regulations and the development of the Commission of Architectural Review, by acknowledging the role historic preservation plays and will continue to play in shaping the city's urban form and character, while recognizing that additional efforts are needed to identify high priority areas for preservation, reinvestment, and economic development.

The first planning phase will require: 1) a detailed analysis of the existing historic preservation planning goals, objectives, and strategies contained in Richmond 300, 2) a thorough examination of the City's historic planning efforts, success, and challenges, and 3) targeted outreach to stakeholder groups and the general community.

Enslaved African Heritage Cam pus

pus

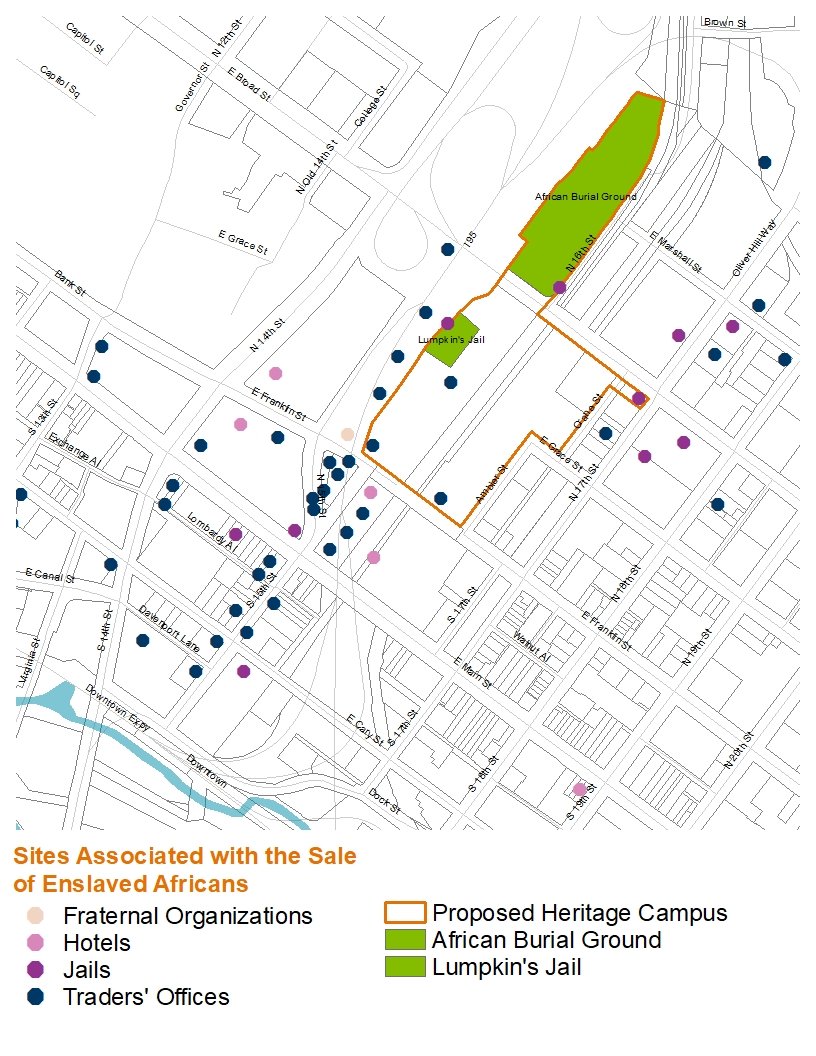

The development of the Enslaved African Heritage Campus is a major component of the Shockoe Small Area Plan. In 2020, Mayor Stoney announced the planning and development of a multiuse, park-like campus that would engage the community and tell the full story of Richmond's involvement in the domestic slave trade and the resilience of enslaved and free Africans. The $38,000,000 project will begin design in 2022 with extensive community outreach and consultation. The two primary elements of the campus are the development of a museum about the domestic slave trade at Lumpkin's Jail site and the creation of a commemorative space at the African Burying Ground. The campus will be a place of reflection and active learning with the mission of expanding the narrative of Richmond's role in the domestic trade in enslaved individuals.

Museum at Lumpkin's Jail Site

A museum, a center for interpretation, at the site of Lumpkin's Jail, will be a major feature of the Enslaved African Heritage Campus. The form the building will take is evolving because of the many difficulties with the desired location, which include an archaeological site, flooding, and an interstate highway. The purpose of the museum, however, is clear and guided by principles set by the community. The museum should tell the full, authentic story of Richmond's involvement in the domestic trade in the enslaved. In 2016, the City entered a contract with the SmithGroup, a Washington, DC, based architectural firm to design a building for the site. Development will be guided by the City.

The National Slavery Museum Foundation will be responsible for the majority of the fundraising, future operations, and management of the museum. In the interim, the City is exploring options to open a museum in Main Street Station in conjunction with other local institutions.

History of Lumpkin’s Jail Site

Robert Lumpkin was the third and last slave trader to own the Lumpkin's Jail Site property. Bacon Tait, one of the most successful slave traders and jail operators in Richmond, acquired the three lots on Wall Street in 1830 where he built a brick dwelling. In July 1833, Tait sold the three lots to Lewis Collier, another slave trader. It is unclear if Tait or Collier constructed the jail, but it was in place when Robert Lumpkin acquired the property in November 1844.

Following the American Civil War and the end of the domestic trade in enslaved persons, Robert Lumpkin and his enslaved “wife,” Mary, ran a hotel on the property. Robert Lumpkin died in October 1866, and left all of his Richmond properties as well as properties in Philadelphia, PA, and Huntsville, AL, to the woman “who resides with me,” Mary Lumpkin. Mary may have continued to run a hotel on the site and supplemented her income by doing domestic work for others. In 1867, she leased the property to an abolitionist Baptist minister, Reverend Nathaniel Colver. Colver repurposed the former slave-trading facility into an educational institute for the formerly enslaved. The Colver Institute, the precursor to Virginia Union University, occupied the site until 1870 when it moved to the United States Hotel at the corner of 19th and Main streets. In 1873, Mary Lumpkin sold the Wall Street lots to Andrew Jackson and Mary Lucy Ford. By 1876, the value of the buildings on the property had dropped considerably to $6,500. The atlas of Richmond published by F.W. Beers the following year depicted buildings along Wall Street on the former Lumpkin lots, but no structures were shown to the rear where the jail had been located.

In 1892, Ford sold the lots to John Chamblin and James H. Scott who with Alexander Delaney established the Richmond Iron Works on the property. In 1905, John Chamblin deeded his share of the Richmond Iron Works property to the Seaboard Air Line Railway. The transfer was not fully complete until 1907, when the executors of James H. Scott conveyed his interest to the railroad. Main Street Station was constructed by the Seaboard and Chesapeake and Ohio Railway in 1901. The ironworks were demolished and the Seaboard Building and its 500 foot warehouse were completed in 1909 on the site. In the late 1950s, the northern section of the Seaboard warehouse was demolished and the Richmond and Petersburg Turnpike (now Interstate 95) was opened through the site in 1958.

Other Sites Associated with the Trade in Enslaved Africans

Richmond’s enterprise in enslaved Africans was second only in volume and value to New Orleans, LA. It is believed that from roughly 1830-1865, between 300,000 to 350,000 enslaved men, women, and children were “sold south” from Virginia, with the majority sold from the many establishments concentrated in Shockoe. It is difficult to fully discern the exact number of businesses directly tied to the trade in enslaved Africans because the businesses went by different names – traders, agents, auctioneers, commission merchants, and brokers – and the individuals and partnerships continually changed. What is known is that by 1860 over 69 entities identified as being participants in the buying, selling, and leasing of enslaved persons. There were also at least seven jails, of which Lumpkin’s was one, that operated between 1830 and 1865. The majority of these establishments were concentrated in a small area in Richmond between 14th, 17th, Broad, and Cary streets in Shockoe. Unlike other cities, Richmond rarely conducted open air sales. Most transactions took place in traders’ offices, at the jails, and in the basements of hotels and fraternal organization buildings. There were numerous other businesses, located throughout the city – tailors, blacksmith, bankers, insurance agents, railroads, and shippers -- that supported and profited from the trade.

Archaeology

The story of Richmond’s involvement in the trade will need to be told almost entirely through archaeology. With the exception of a few warehouses and businesses that owned or leased the enslaved, the majority of the buildings linked directly to buying, selling, and leasing have been systematically removed.

In late 2005, the James River Institute for Archaeology (JRIA) began gathering documents and started an archaeology investigation of the Lumpkin’s Jail site in order to establish its location and assess its archaeological integrity. The critical first task was to determine as accurately as possible the location of Lumpkin’s property on Wall Street, long since buried beneath Interstate 95 and the paved parking lots behind Main Street Station. Intensive documentary research was conducted, and the detailed 1835 Bates Map was georeferenced onto modern maps, and a survey team marked the locations of Lumpkin’s lots in the field, clearly showing that Wall Street and the western portion of Lumpkin’s lots, including his dwelling and the hotel, were buried beneath Interstate 95 but there was a strong possibility that the rear eastern portion of the lots, including the jail, were beneath the parking lots to the rear of the Seaboard Building.

In late 2005, the James River Institute for Archaeology (JRIA) began gathering documents and started an archaeology investigation of the Lumpkin’s Jail site in order to establish its location and assess its archaeological integrity. The critical first task was to determine as accurately as possible the location of Lumpkin’s property on Wall Street, long since buried beneath Interstate 95 and the paved parking lots behind Main Street Station. Intensive documentary research was conducted, and the detailed 1835 Bates Map was georeferenced onto modern maps, and a survey team marked the locations of Lumpkin’s lots in the field, clearly showing that Wall Street and the western portion of Lumpkin’s lots, including his dwelling and the hotel, were buried beneath Interstate 95 but there was a strong possibility that the rear eastern portion of the lots, including the jail, were beneath the parking lots to the rear of the Seaboard Building.

In 2006, JRIA conducted the archaeological component of the investigation by defining a testing area and excavating three trenches. The layer associated with the Lumpkin occupation of the site was encountered at depths ranging from 5 to 10 feet below existing grade across the site with the lowest areas located at the southern end. The testing indicated that mid-nineteenth century cultural deposits and features evidently associated with Robert Lumpkin’s domestic and commercial complex survived intact beneath later fill and destruction layers. No definitive evidence of the jail building itself was found; however, at least two significant features were identified, including a cobble-paved surface and possible boundary fence. In addition, it appeared that the preservation within this sealed context was excellent, with organic materials such as wood and leather surviving in remarkably good condition. The excavated trenches were backfilled and the site area protected pending further investigation.

In August 2008, JRIA began the archaeological data recovery project at the Lumpkin’s Slave Jail site. During the course of the excavation, JRIA removed between eight and 15 feet of fill within the excavation area, exposing a wide variety of historic features spanning the occupation of the site from the 1830s through the mid-twentieth century. The remains of the jail building foundation were found at the lowest level of the site, but work could not be continued because of the excessive infiltration of ground water. This phase of excavation revealed an expansive cobble paved surface and other sensitive features, such as the kitchen and jail building foundations and the retaining wall that separated the upper and lower terraces. The decision was made to intentionally rebury the site to protect the archaeological site from the inevitable damage caused by exposure to the elements and other disturbances.

The First African Burying Ground

The exact establishment date of the “Burial Ground for Negroes” and its location in the modern landscape are uncertain. Speculation ties its creation to William Byrd’s Falls Plantation prior to the establishment of Richmond in 1737. Other theories suggest that it was established in 1751, when the white municipal cemetery was established at St. John’s Church. The first and only known recorded burial was of Sally Anderson, “a poor free negro woman," in January 1795. Gabriel, an enslaved man who led a well-known rebellion in Richmond, was hanged at the gallows located in the burying ground and interred there in 1800. Richmond’s earliest burial ground for enslaved and free blacks was in use until 1816 when a new burial ground opened just outside the city limits to the northeast of the white protestant Shockoe Hill Cemetery and east of the white Hebrew Cemetery.

The location of the burying ground is similarly uncertain. It was an informal, unenclosed, cemetery of indeterminate size situated on common land and private property along the west bank of Shockoe Creek and north of Broad Street. Richard Young’s, “A Plan of the City of Richmond”, ca. 1809, provides the only mapped location, and Christopher McPherson’s autobiography provides the only known contemporary description from 1811. During the 1820s and 1830s, the area was subject to large-scale grading and terracing efforts to accommodate development in the area, including a new city jail. Shockoe Creek was also shifted to the east straightened and channelized during this period. Shockoe Creek was further altered in the mid-1920s when it was buried and enclosed in a conduit. Today, the vast majority of the burying ground likely lies below Interstate 95 constructed through the area in the 1950s.

Buried and significantly lost to public memory, interest in and understanding of the burial ground began to resurface in the early

2000s. Research by a local historian shed light on its possible location to the east of I-95. In 2004, attention was drawn to the

area as the final resting place of Gabriel and a historic highway marker was erected nearby. In 2008, VCU/MCV purchased a

parking lot at 16th and Broad, which brought public protest opposed to the paving atop gravesites. As a compromise, a small area where graves might extend past I-95 was enclosed and not paved. In May 2011, the Commonwealth of Virginia transferred

the parking lot to the City of Richmond, the asphalt was removed, and sod installed. The Richmond Slave Trail added signage to the

burial ground in 2011, which is the second to last stop on the trail that tells the story of Richmond’s involvement in the international

and domestic trade in enslaved Africans. The Sacred Ground Historical Reclamation Project, long involved with the recognition of the burial ground, produced proposals for the Shockoe Bottom Memorial Park in 2015 and 2017, which will be incorporated in the City’s Heritage Campus.

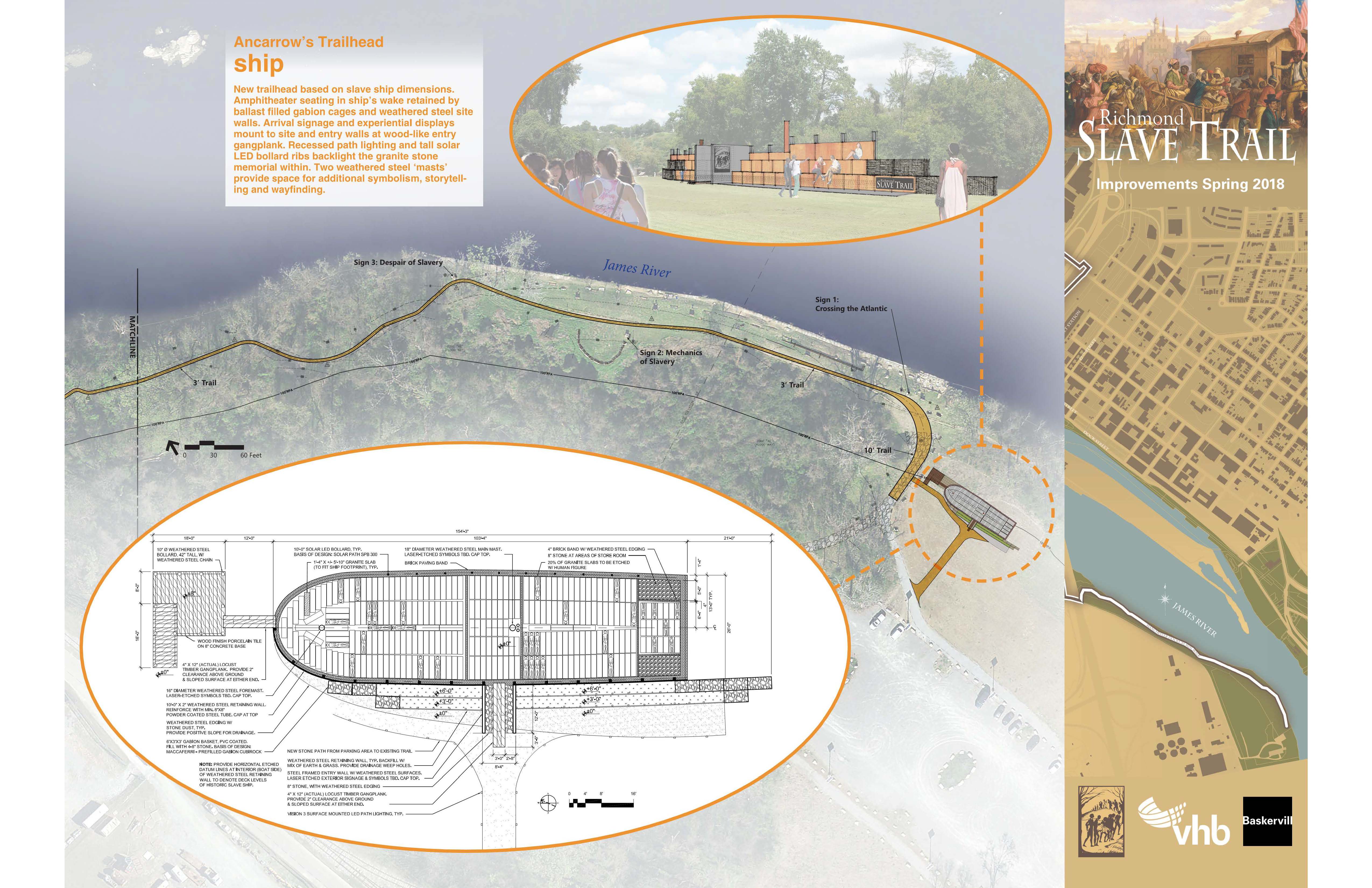

Slave Trail Improvements

A new trailhead based on life-size slave ship dimensions has been proposed as an addition to the Richmond Slave Trail. To learn more, click here.

Designed as a walking path, the Richmond Slave Trail chronicles the history of the trade in enslaved Africans from their homeland to Virginia until 1778, and away from Virginia, especially Richmond, to other location in the Americas until 1865. The trail begins at the Manchester Docks, which, alongside Rocketts Landing on the north side of the river, operated as a major port in the massive downriver slave trade, making Richmond the largest source of enslaved blacks on the east coast of America from 1830 to 1860.

The proposed Ancarrow’s Trailhead Ship would enhance a critical component of this journey by creating a space for additional storytelling and wayfinding.

To learn about more proposed improvements to the Richmond Slave Trail, click here.

To view a full map of the Slave Trail, click here.

Winfree Cottage

From 1866 to 1893, this little cottage was the home of Emily Winfree, an enslaved woman, who rose above her oppression and built a life and home for herself and her children in the Manchester community of Richmond. In 2002, this tiny, two-room cottage was moved from the intersection of Porter and Commerce Streets in Manchester to Shockoe to save it from demolition. For the past 20 years it has sat on a trailer waiting for a permanent home to be found. Through a partnership with the City’s Department of Parks and Recreation, the Virginia Museum of History and Culture, and descendants of Emily Winfree, the cottage will be moved to a new location in Manchester, which will allow the cabin to be accessible to schools and visitors.

From 1866 to 1893, this little cottage was the home of Emily Winfree, an enslaved woman, who rose above her oppression and built a life and home for herself and her children in the Manchester community of Richmond. In 2002, this tiny, two-room cottage was moved from the intersection of Porter and Commerce Streets in Manchester to Shockoe to save it from demolition. For the past 20 years it has sat on a trailer waiting for a permanent home to be found. Through a partnership with the City’s Department of Parks and Recreation, the Virginia Museum of History and Culture, and descendants of Emily Winfree, the cottage will be moved to a new location in Manchester, which will allow the cabin to be accessible to schools and visitors.

In June 2022, the City of Richmond dedicated $500,000 to the relocation, restoration, and interpretation of the cottage. Next steps will include community engagement.

Who was Emily Winfree?

Emily (1834-1919) was born enslaved in 1834, the date given on her gravestone, but there are conflicting accounts which place her birth year between 1837 and 1842. There is no record of Emily’s life until 1857 when she was listed as the property of Jordan Branch, a lawyer and sheriff in Petersburg, Virginia. In the 1857 inventory of Jordan Branch’s estate, Emily is listed as twenty years old, the child of Mary Ann, and having a daughter of her own, Maria. The combined appraised value for mother and child was $800. Emily and her daughter were sold at auction on December 28, 1858 to Mr. A. B. Hutchinson for the sum of $1,025. Emily may have been pregnant at the time of her sale, for in 1859 or 1860, she gave birth to a second daughter, Elizabeth (Bettie). On the 1860 Schedule of Slave Inhabitants, Emily and her two daughters are listed along with 44 others as being owned by David Winfree, who was Jordan Branch’s brother-in-law.

Between 1853 and 1860, David Winfree fathered at least seven children with women owned by his family. It is not known if David Winfree was the father of Emily’s two daughters, Maria and Bettie, but she had three more children while she was owned by him – Walter David (1862), James Wiley (1865) and Henry (1866). In June 1864, David enlisted in the Confederate army but was discharged in early 1865 suffering from Syphilitic rheumatism. Realizing his death was imminent, David tried to auction his 548 acre farm on Falling Creek. No buyer was found for the property so he advertised for an overseer with the enticement of “an excellent washer, cook, and ironer with four small children.” On March 14, 1866, David purchased a small house in Manchester for Emily and her children, and two months later granted her a 109.5 acre tract of his farm and gave her exclusive rights to both properties. David also named a trustee, which complicated and encumbered any actions Emily might wish to take with the land. On March 20, 1867, David Winfree died.

In the summer of 1867, Emily petitioned the courts of Chesterfield County to allow her to cut timber off of her 109.5 acre tract and build a house. She lived in the country and rented the house in Manchester, but by 1870 she moved back to Manchester. Emily gave birth to another son, Clifford, in 1869, and a daughter, Lucy, in 1877/78. The father or fathers of these two children are unknown. Emily was employed by the Masonic Manchester Lodge #14 for thirty-three years to prepare meals for meetings and events. As this was not full time work, she would have worked other jobs to provide for her family in addition to the rent received from the second house on her Manchester property. The children also held jobs to support the family.

Emily and other members of her family were stricken with a serious illness in 1885 and 1886, which led to her selling the second house on her lot in Manchester, taking a loan on the other, and selling her land in the country. These transaction were complicated and costly because of the trustee. In 1893, Emily was able to buy a larger house in Manchester at 16th and Stockton streets where she resided until her death. She sold the cottage in 1905. Emily died on January 10, 1919 and is buried nearby at Maury Cemetery.

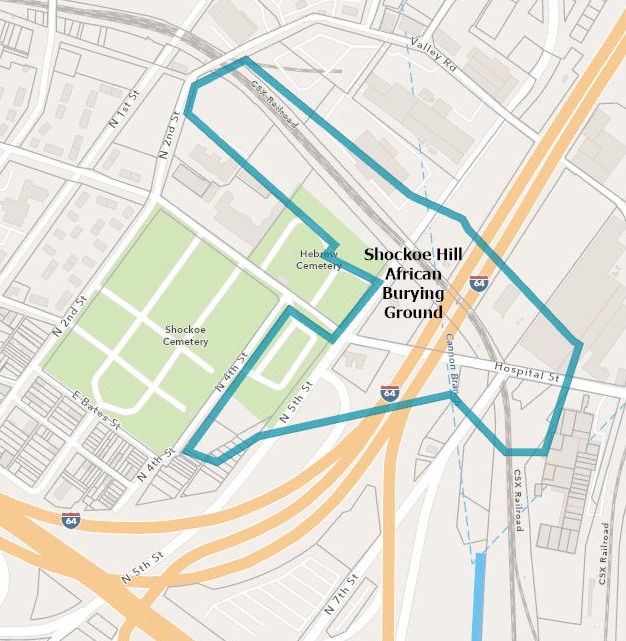

Shockoe Hill African Burying Ground

In 2021, the City of Richmond acquired 1.2 acres of the original two acres of the Shockoe Hill African Burying Ground. In June 2022, the City of Richmond dedicated $500,000 to begin the process of memorializing the Shockoe Hill African Burying Ground. The first phase of this project will involve community engagement, which will influence the continued planning process.

You would not recognize the parcel at 1305 N. 5th Street with its abandoned gas station and large billboard as a cemetery. This property is part of the original two acres set aside by the City for the “grave yard for free people of colour and for slaves.” It was the city’s second municipal cemetery for its black population both free and enslaved. It was in active use as a cemetery from 1816 to 1879, and the expanded property is believed to be the final resting place for approximately 22,000 free and enslaved blacks, poor whites, and criminals. The contrast between the Shockoe Hill African Burying Ground and the two adjacent white cemeteries speaks loudly to the value placed on people in life and in death.

The first move toward establishing a formal burying ground on the property came in 1810. Christopher McPherson, a free black, petitioned the city for a new burial ground for the city’s black inhabitants because conditions at the burying ground in Shockoe Bottom were so deplorable. By 1816, the city had set aside two acres on the northeast corner of Hospital and Fifth streets for use by “free people of color” and “slaves.” A one-acre cemetery for the City’s Jewish population soon followed on the northwest corner of Hospital and Fifth streets, and the larger, 4-acre, cemetery for the City’s white protestant population was located south of Hospital Street between 2nd and 4th streets.

In 1849, nine acres were added to the Shockoe Hill African Burying Ground. A burial ground for “paupers and strangers” was also designated at this time. The only known written description of the Shockoe Hill African Burying Ground was made by Frederick Law Olmstead in 1853 during his tour of the South to assess the impact of slavery on the region. He described it as a “desolate place”. Olmstead described a new grave being dug “near the foot of a hill in a crumbling bank – the ground below being already occupied, and the graves apparently advancing in terraces up the hill-side.”

The destruction of the Shockoe Hill African Burying Ground began in the closing days of the American Civil War and continued well into the mid-twentieth century. The explosion of the powder magazine on the morning of April 3, 1865, caused the loss of lives, extensive property damage, and unearthed buried remains. The construction of two new magazines displaced more burials. The cemetery was closed to new burials in 1879. The extension of 5th Street and the construction of a viaduct to carry trolley cars to the northern suburbs in the 1880s reshaped the topography of the Shockoe Hill African Burying Ground by cutting down the plateau it occupied. The Seaboard Airline Railway was constructed to the north and east along the bottom of the slope of the burying ground. Hospital Street was realigned to the northeast and the gulley to the south filled, which impacted the southern portion of the burying ground. A newly created, level parcel, south of Hospital Street was set aside for the construction of a dog pound. The remaining portion of the original two-acre burying ground was sold in 1960 to the Sun Oil Company, and in 1965 the eastern portion was sold for the right-of-way of Interstate 64. The eastern slope of the burial ground was cut down at the property line for the construction of the highway. For additional information refer to the National Register Nomination.